True and Fascinating Canadian History

A Magnificent, Monumental, Memorable Mystery

Part III : May 2011

by J. J. (Joe) Healy, RCMP Superintendent, (Rt'd)

Police Officer, Historian and Friend

January 1, 1931 to February 22, 2011

Jack now knows the secret answer to a tremendous Canadian mystery

A Mystery Series

Part III

Murder: 'No Small Matter'

Educators, parents and the average Joe are perpetually worried that today’s school children are not being strenuously taught about the value of Canadian history. As evidence, only one history course is mandatory in Ontario high schools. That in itself seems out of whack. Canadian history is out of style. It’s become old fashioned, relegated to the archives. Some argue there’s not enough time for history. I firmly hope there will be a revival of interest in history. Perhaps the problem lies in the human brain and its capacity for memory. After all, the brain is miraculous, but it has limits. I propose we look at another species for a new model of learning.

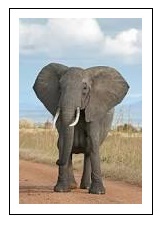

Canadians should look to elephants as a valuable source of inspiration. Elephants are reputed to have unusually highly developed memories. At least, clinical science says so. Apparently, the number of folds in their grey matter contributes to this remarkable phenomenon. In brief; more folds, more space, more capacity, more memory. This well-known elephant trait seems well out of the ordinary given the fact that people are highest among all mammals in the evolutionary chain.

Yet, the memory capacity of humans is remarkable and far out distances an elephant provided it is exercised properly. This well tested observation of people and memory is certainly valid even in the early stage of human life. Very young children, for instance, can learn multiple languages more easily than adults. I have a little friend about five years of age. He speaks Arabic to his father and Spanish to his mother. He rambles in English to his friends and he is schooled in French. He amazes me. Somehow, his brain’s ability is remarkable but not highly unusual. Some children learn how to spell, articulate and demonstrate uncanny mental exercises with great success at a very early age. The work of their little brains seems unlimited. Their memory and recall is impressive. Ask grandparents. Observe elephants.

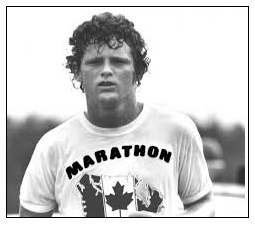

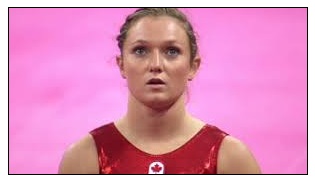

Unfortunately, Canadians tend to easily forget our Canadian heroes. How many of the following people do our young people recognize; Emily Murphy, Georges Cartier, Louis Papineau, D'Arcy McGee, Simon Fraser, Sir Frederick Banting, Sir Sandford Fleming, George Brown, Pauline Johnson, Sir Arthur Currie, Brother Andre, Marc Garneau, Julie Payette and Rick Hansen -- just to name a few?

All are famous Canadians. Each person has contributed greatly to the development of Canada and its culture. As a people, I know that we are proud of them. But, by in large, the general tendency of many Canadians is not to know the remarkable story that lies behind the name. On the Shakespearian scale, let’s agree that to forget our heroes and their stories is a tragedy.

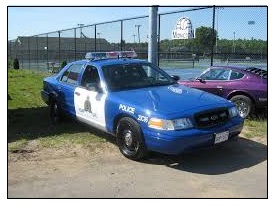

Here’s one example. I’ll turn to a famous and worldwide Canadian institution; the RCMP. Down through the years, there have been volumes written about the RCMP, its history and its exploits. But, by far, less is known about the police personalities involved in these famous exploits. In broad terms, many Canadians know about the role of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) and the March West but few would be able to identify individual members of the Force who actually participated in this grand event; Cherry, Bray, Crozier and Jarvis.

It is a shame that Canadians do not pay sufficient attention to the characters that are mentioned in cursory fashion in our history books. Perhaps excepting for the larger than life names of Sam Steele and Henry Larson most Canadians would be hard pressed to name great and noteworthy members of the RCMP who have played pivotal roles in some of our country’s most memorable milestones.

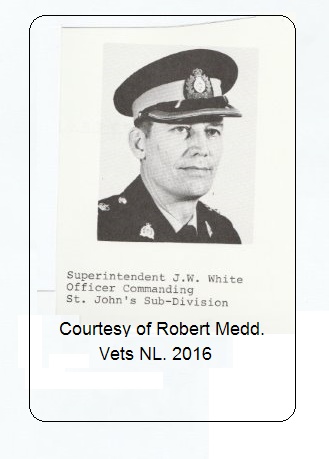

As a young constable through the 1960’s, I was exposed to yarns and story-telling in ‘Depot’ Division by instructors such as Sergeant Tom Forster. I recall stories told by senior members at the various Detachments to which I was assigned. One story teller was Sergeant Eric White. He was my NCO in Maple Ridge Detachment outside Vancouver, BC. Sgt. Eric White and recently deceased Superintendent Jack White (no relation) successfully solved a brutal murder in Coquitlam, BC. I listened with intense interest to the tall tales of times past. I learned to appreciate the trials and tribulations, triumphs and tragedies of situations faced by members of the Force at various times. As often happens, I learned more about the situation and less about the personalities directly involved in the case.

For instance, I knew about the North West Rebellion, Duck Lake, the Klondike days, the construction of the CPR and the Winnipeg Strike -- the causes, the outcomes, the statistics -- but I could not identify the members who fought or were killed in the midst of these mostly hazardous episodes. Also, I knew the RCMP was involved in Canada’s major overseas ground conflicts; the Boer War of South Africa, the World Wars and Siberia. I knew as well the RCMP’s contributions to the Canadian Navy and the Canadian Air Force during war time. But, like others, I could not picture a member of the RCMP in Red Serge who actually took part in these activities. Many of the RCMP’s dead are buried in overseas cemeteries; Belgium, England, France, Ireland, Italy and South Africa.

In 1971, however, a particular situation involving the RCMP of decades ago came to life for me. It deeply changed the way I viewed Canadian history and the nation-building role which the RCMP played. The personalities involved in the case imprinted themselves on my mind in a way that left lasting and remarkable impressions. I was involved in a seemingly small incident. At the time, I could not forecast how it would connect me to a famous murder case which had happened many decades earlier. A member of the Force was the victim. These memories have stayed with me for the remainder of my life. The murder has direct implications to the mystery which is now unfolding. Now, I’d like to tell you the story.

After several years in policing on Canada’s west coast, I was transferred to Prince Edward Island. May 24, 1971 was a most unusual day on Prince Edward Island. It was a long weekend. I was posted to Charlottetown Highway Patrol and, as expected, traffic was heavy. I was assigned to Highway Patrol duties in Queen’s County – some miles outside Charlottetown. Without warning, the Island experienced an unusual, sudden, wild, fierce and heavy snow storm. I was working alone, and unexpectedly I was involved in the investigation of several car accidents on the Trans Canada. The storm worsened. At noon, highway visibility was zero. As a result, I forced other motorists to stop driving and pull over until the weather cleared. The strategy worked. Because of the present danger, RCMP supervisors ordered all police patrol cars off the highway. With the aid of emergency lights, I crept along until I arrived at downtown Charlottetown ‘L’ Div. Headquarters.

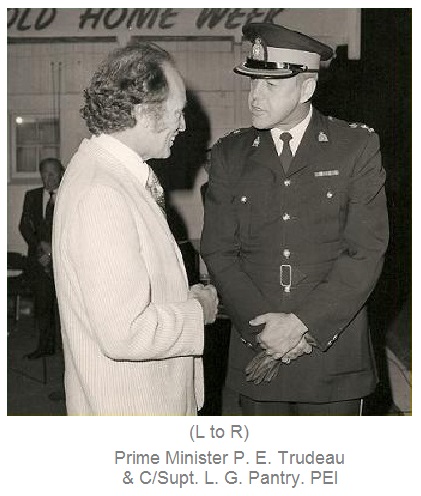

On this blizzard afternoon, I was working alone in the Highway Patrol office. Earlier in the day, I had heard Superintendent Pantry come active on the police radio. I realized that he, too, was somewhere on patrol. As the storm worsened, I became concerned, but I knew that he wasn’t in danger. Although I was curious, I couldn’t guess his location. It wasn’t my business to ask. I didn’t anticipate it, but in a matter of minutes, Supt. Pantry and I were about to meet again.

About 2PM that afternoon, Supt. Pantry suddenly burst into my office. He was unusually excited. He clutched an envelope. He was very, very upbeat and he anxiously wanted to show the file to me. As it happened, the envelope in his hand contained the original file of a very, very celebrated RCMP case of many decades ago. At first, his anxiousness was a mystery to me. I became more and more curious. Years ago, someone in the RCMP had understood the historic value of this particular police file. Someone had set the file aside saving it from destruction. Someone wanted to preserve its history.

Now, in the company of Supt. Pantry, I was being invited to peruse the entire original RCMP reports from decades past. The reports in the file had been signed by all the members involved in the case.

Supt. Pantry told me that the RCMP file had been given to him by a friend, but at the time, he would not divulge the person’s name. That’s a topic for another mystery. Anyway, we thumbed through the file together -- we treated it delicately -- I’d guess about one hundred pages --the file also contained the remarkable original photographs of the suspect from the case.

The file was too long to read thoroughly in one afternoon. Soon, the snow storm abated. I was expected back on the highway. But, I was anxious to review the file page by page so Supt. Pantry allowed me to secure the file overnight. I had to promise that I would deliver the file to his desk early the following morning. His intention, he said, ‘…was to mail this [remarkable] file to Archives Canada in Ottawa.’ As soon as I was alone, I immediately photocopied the file. The file was valuable as well as historical. Early the following morning, I delivered the original file to Supt. Pantry in his office. He asked whether I had sufficient time to read it, adding, “No worry, Constable Healy, I’m sure there will be time later for you to finish it.” We laughed. Supt. Pantry knew me too well. He had wisdom and experience.

Indeed, on my own I did review this file. I read it again and again and became more and more captivated by the story. It was at this time that I began to appreciate the reality of the personalities connected to a tale not only well known in the Force, but known as well around the world.

From the pages of the file which I studied in detail I felt that I befriended certain heroes of the Force. These heroes in alphabetical order are:

Superintendent A. E. Acland - Commanding Officer ‘G’ Division, Edmonton, AB.

Special Constable J. Bernard - Posted to Arctic Red River Detachment

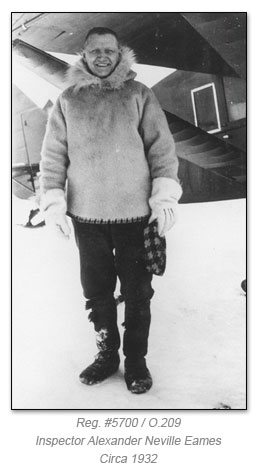

Inspector A. N. Eames - Officer Commanding, The Western Arctic Sub Division

Cst. A. W. (‘Buns’) King - Posted to Arctic Red River Detachment under Constable Millen

Sir J. H. MacBrien, K.C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O -- Eighth RCMP Commissioner. 1931-1938

Constable E. (‘Spike’) Millen -- Constable In Charge of the Arctic Red River Detachment, N.W.T

Constable R. G. McDowell -- Posted to Arctic Red River Detachment Under Constable Millen

Corporal R. S. Wild - Admin. Assistant in Aklavik, N.W.T. to Inspector A. N. Eames

Special Constable L. Sittichiulis - Posted to Aklavik. On loan to Constable Millen

So, to which file am I referring?

Many people may have already guessed that it is none other than the famous

‘Tale of the Mad Trapper’

How could it be any other?

Over the years, I have read and re-read the file and the actions of each person in their role in the pursuit of ‘The Mad Trapper.’ It is a case which did capture the imagination of a worldwide audience. At the time, there was a boom in the purchase of radios so that the pursuit of the killer and the RCMP’s progress could be followed. The story could make a unique Canadian history case to study for generations of our youth.

Due to space limitations, the list of the RCMP which I identify is exclusive. Other RCMP were mentioned in the file but were not so directly involved in the actual pursuit. I also truly acknowledge that many, many other people honourably and bravely contributed to the final outcome of ‘The Mad Trapper case’. For instance, WWI Ace and bush pilot ‘Wop’ May’s flying ability in life threatening weather conditions was outstanding and incredulous. The Royal Signals Corps in the north sent volunteer searchers.

The Corps also provided radio communications. History of the RCMP was marked during the pursuit because it was the first time that an airplane had been used in the pursuit of a police suspect. The invaluable help of ‘Wop’ May and the airplane contributed to the formation of the RCMP ‘Air’ Division in 1937.

There were injuries and medical experts saved lives. Others involved in the pursuit were former RCMP members, RCMP Guides, civilian volunteers and the Native People. Others in the case included; clergy, witnesses, jury members, grave diggers and carpenters. One way or another, the ‘Mad Trapper case' emotionally marked these people for the remainder of their lives. Each person who aided the RCMP also remained faithful to the RCMP until the pursuit was over. This story as I tell it is memorably dedicated to all these people. Thank you.

Truthfully, however, one could say today that the file remains open. The killer has never been positively identified. There are unlimited theories. His identify, his motives, background, evasive strategies, his apparent hate for the police, his money,his expert use of weapons, his super strength, his rock climbing skills and his determination are still being researched and talked about. Several fascinating books on the case have been written by Canadian authors.

I never tire to learn more about the RCMP who were involved and their work conditions. In 1931, the RCMP lacked effective communications. The case became the largest manhunt in Canadian history. The pursuit covered unusually large geographical distances under the harshest of weather conditions. Reports from popular books say temperatures were about minus 40C to minus 50C. Severe deadly cold wind was always present. Imagine the energy expended to drive a dog sled over treacherous snow and ice in heavy winter clothes at those temperatures. If one stopped for a moment, perspiration turned to ice. Week after week, men had to endure the perils of the Arctic cold. Death was nearby. One person depended on another.

Persistence, bravery and survival skills have to be hallmarks of their efforts. Food was scarce for both men and their sled dogs.

Great care had to be taken with the sled dogs. They had to be kept secure. Each dog ate an abundance of food which also had to be transported. Dogs were required to transport the injured to hospital and haul supplies over the long pursuit. The high probability of an ambush haunted the men. The environment was mostly stormy with high winds. I have given a lot of thought to the cold, dark, isolated wilderness which men faced during this pursuit. I’ve thought also of the quirky Maritime spring storm which had led me to be exposed on a far more personal level to this story. The Maritime storm quickly passed. Not so, in the Arctic. Every person in the north could tell a tale about the dangers of living in the Territories and the toll of the cold.

The tale and pursuit of ‘The Mad Trapper’ by the RCMP became a legend which fascinated a worldwide audience. In the ensuing years, hundreds of books, articles, research papers, movies and interviews have been produced.

Now for those who may not know, it is essential to become familiar with the outline of this story.

Who was ‘The Mad Trapper’ and how and for what reasons was he chased?

'The Tale of the Mad Trapper’

Arctic Sub-Division Reference #37-8. [1931 and 1932]

Note:

The method which I followed for the compilation of this story was to use a copy of the actual police report. Normally, a police report is purposely bland. The questions to be probed by the investigators are these; who, what, where, when and how many? These are the issues important to the judiciary. The use of adjectives, minute descriptions, weather conditions, the precise location of the moon in the sky, the colour of the dogs and harness and romantic notions are not part of a police report -- that is the job of journalists, researchers, authors, students and others.

To learn more about ‘The Tale of the Mad Trapper’, I encourage the reader to find the books which I list in the bibliography. If the reader finds any fault with the following presentation of the case, I kindly ask you to tell me. I will provide a copy of the file page from which my details originate.

I use [ ] brackets to insert or repeat names to help the reader.

In 1931, there were scant few RCMP in the Western Arctic. The full complement consisted of about eleven RCMP of various ranks under the command of one Officer, an Inspector.

The case began on July 12, 1931. A memo from Reg. #7536, Corporal Richard S. Wild, in Aklavik, NWT Assistant NCO on behalf of the Commanding Officer, Officer #5700, Inspector A.E. Eames was sent to Reg.#9669, Constable E. (‘Spike’) Millen, Constable In Charge of the Arctic Red River Detachment, ‘…it has been reported that a strange man going under the name of Johnson landed somewhere near Fort MacPherson on the evening of Thursday, July 9th, 1931.’

The memo said that Johnson arrived on a raft and that he owned very little kit but he had lots of money. Johnson had purchased supplies in MacPherson and he had enquired about the route into the Yukon. Constable Millen was asked to make enquiries about Johnson whenever he was in the area of Fort MacPherson.

Constable Millen replied to Inspector Eames on September 11, 1931. Constable Millen reported the following;

• he [Cst. Millen] met a man who identified himself as Albert Johnson on July 21, 1931 in Fort MacPherson,

• Albert Johnson told Cst. Millen that he had worked the previous summer and winter on the Prairies and that he arrived at Fort MacPherson via the MacKenzie River,

• Cst. Millen informed Albert Johnson that if he intended to stay in the MacPherson area, he would require a hunting licence which could be purchased at the Arctic Red River Detachment or in Aklivak. Johnson replied that he was undecided about his future plans,

• Albert Johnson told Cst. Millen that rather than live in Fort MacPherson, he preferred to live alone in the bush and that he didn’t want to be bothered by others. Cst. Millen found Johnson to be evasive in his replies. Johnson told Cst. Millen that if he [Johnson] did not stay in the area, that it was not necessary for the RCMP to know ‘all about him’. Cst. Millen did not follow up any further questions with Johnson,

• Later the same day, Cst. Millen interviewed Mr. Douglas, the Northern Trader at Fort MacPherson. Cst. Millen learned that Johnson was assembling some kit for a portage and that Johnson had purchased a canoe and other goods at the Hudson Bay Co.

• Mr. Douglas and Mr. Middleton, both of the H.B. C. told Cst. Millen that Johnson ‘…comes in and gets what he wants and pays for it and bothers no one.’

• In his report, Cst. Millen summed up that Johnson had no definite plans, that he [Cst, Millen] would re-interview Johnson again when he visited Fort MacPherson to determine where Johnson intended to settle. Constable Millen’s report was received by Inspector Eames. On August 11, 1931, Inspector Eames personally wrote a lengthy memo to Constable Millen.

Inspector Eames told Cst. Millen that he [Eames] was surprised that he [Millen] had accepted Johnson’s excuse for being evasive about his travel plans. Inspector Eames explained that it was important for the RCMP to know the intended address of men coming into the north in the event there was an accident or if a person was reported as lost. Cst. Millen was told to ‘…keep track of Johnson…’.

Further, Inspector Eames said, that under suspicious circumstances or, if necessary, the RCMP has the right to search a person’s kit under the Games Regulations. Johnson, instructed Inspector Eames, was to be encouraged by Cst. Millen to communicate with the RCMP about his whereabouts and his conditions as this was a common practice after ‘…the death of Nicol and Beaman on the Gravel River.’

In his conclusion, Inspector Eames said that if Johnson intends to travel to the Yukon, he should ‘…drop you (Cst. Millen) a line acquainting the RCMP of his safe arrival as this help to the RCMP can prevent long police patrols which sometimes are unnecessary.'

The next RCMP memo was written by Reg.#10269, Constable R. G. McDowell on January 2, 1932. Cst. McDowell said that he had acted on instructions from Inspector Eames and that he left Aklavik at 7:30AM on December 30, 1931 along with Reg.#10211, Constable A.W. King and Special Constables L. Sittichhiulis and J. Bernard. The destination of the RCMP patrol was the cabin of Albert Johnson which was situated on the Rat River near Destruction City, so called after many miners had perished on their way to the Yukon Gold Rush of 1898.

In his report, Cst. McDowell said the patrol (consisting of the four RCMP; McDowell, King, Sittichiulis and Bernard) reached Albert Johnson’s cabin at 10:30AM the following day which was December 31, 1931. Cst. McDowell approached Johnson’s cabin just as Cst. King knocked on Johnson’s door, at the same time shouting …’are you there Mr. Johnson?' There was an immediate shot through the door from inside the cabin. The shot hit Cst. King who fell, then got up and staggered into some bushes.

Cst. McDowell was able to secure his own rifle and began to shoot at the cabin so as to distract the occupant(s). Cst. McDowell was nearly hit by rifle fire on two occasions as he moved in the direction of Cst. King. In the meantime, Special Constable Sittichiulis was first to reach Cst. King. After reaching Cst. King, Cst. McDowell evaluated Cst. King’s condition as serious.

Cst. McDowell made the decision to immediately abandon an attack on the cabin. Instead, the patrol would strap Cst. King in a dog sled and race towards Aklavik. The patrol travelled all night and twenty hours later, they reached Aklavik. The date was January 1, 1932. Cst. King was admitted to All Saints Mission Hospital where he was attended by surgeon Dr. Urquhart.

Inspector Eames was told of Cst. King’s condition and how the police patrol to Johnson’s cabin unfolded. In turn, Inspector Eames sent a telex dated January 1, 1932 to Superintendent A. E. Acland –Commanding Officer ‘G’ Division, Edmonton, Alberta. Inspector Eames reported on the condition of seriously injured Cst. King.

Further, Inspector Eames reported that a complaint had been received by the RCMP of Johnson hunting without a games licence and of interfering with Indian trap lines. He concluded by revealing in the telex that ‘…McDowell brought King [to] Akalvik travelling eighty miles [in] twenty hours. Surgeon [Urquhart] reports bullet entered two inches below left nipple and emerged same place on right side. Am leaving to arrest Johnson when dogs rested probably Sunday morning.’

Over a matter of hours, a somewhat routine interview of Albert Johnson turned into a Criminal Code matter; Attempt Murder of a Police Officer. No small matter. Albert Johnson was a wanted man.

On January 12, 1932, Inspector Eames sent another telex to Superintendent Acland. In his detailed message, Inspector Eames said that he had led a new patrol to Johnson’s cabin and his group also consisted of: Constables Millen and McDowell, Interpreters [Special Constables] Bernard and Sittichiulis, three civilians and an Indian guide.

Inspector Eames said that due to poor information which was given to the guide, he and the group arrived at Johnson’s cabin on January 9, 1932. On approach to the cabin, the group was fearful of an ambush and that the area afforded little protection except for the banks of the [Rat] river. Johnson was commanded to leave the cabin but he refused. A decision was made to rush the cabin, but it was unsuccessful due to heavy fire from two automatic pistols from within. However, the door to the cabin was smashed with rifle butts and a quick peek inside revealed that the cabin was dug out five feet below ground level.

Gunfire continued between Johnson and the police patrol for fifteen hours during which time Johnson had time to repair and close the door. At three AM, the party used high explosives which blew in the door again and caused a hole in the cabin’s roof. Another rush to the cabin by the group failed. The patrol had expected that Johnson would be stunned by the explosives but instead his gunfire was increasingly strong. Inspector Eames speculated that Johnson likely had found shelter from the explosives by extending the limits of space under the cabin.

By this time, dog provisions were running low and other supplies for the patrol were depleted. Inspector Eames made the decision for the group to return to Aklavik. They arrived in Aklavik at four PM on January 12, 1932. In his telex, Inspector Eames said that no one in the group had been injured and that he would be returning to the cabin as soon as he could assemble a larger volunteer party. The next time, he said, a base camp would be established near the mouth of the Rat River.

On January 16, 1932, Inspector Eames’ Assistant, Corporal R. S. Wild sent a telex to Superintendent Acland in Edmonton, AB saying that Inspector Eames had left Aklavik for the Rat River early that morning.

On January 31, 1932, Inspector Eames reported via telex to Superintendent Acland that Staff Sergeant Riddell of the Royal Canadian Signals had been placed in charge of a search group which included Cst. Millen.The search party found Johnson and Johnson fired on the group. The party took cover. Civilian Gardlund fired at Johnson when Johnson exposed himself from behind shelter.

Mr. Gardlund thought that he had hit Johnson, perhaps wounded or killed him. There was no further gunfire for the next two hours and the group felt that Johnson was incapacitated. The group decided to carefully approach Johnson’s position from different angles. The party consisted of Cst. Millen, Staff Sergeant Riddell and civilians Verville and Gardlund. When the party got to within twenty five yards, Johnson opened fire and Millen was struck and fell. The remainder of the group was able to rescue Cst. Millen but he soon died.

The three remaining men guarded Johnson’s position so that he could not escape. Upon receiving word of the death of Cst. Millen, Inspector Eames began to rush every volunteer to the scene which he could muster. Inspector Eames also recommended that an airplane be requisitioned with Captain May as his preferred pilot. He said the plane was necessary as a search party could not remain in the field too long without provisions. Inspector Eames closed his telex by advising Superintendent Acland that he intended to leave Aklavik with the new pursuit party on Monday, February 1, 1932.

February 3, 1932. A telex was sent to Inspector Eames by Superintendent Acland. Inspector Eames’ request for an aircraft to assist in the pursuit of Johnson was approved by Commissioner Sir James Howden MacBrien. In the telex, Commissioner MacBrien instructed Inspector Eames to have Cst. Millen’s body transported part way out of the north by aircraft and then transfer it by rail into Edmonton. The Commissioner also wanted an update on Cst. King’s condition. Finally, the Commissioner told Inspector Eames to take Johnson’s fingerprints ‘…after capture whether dead or not and forward them quickest method.' The true identity of Johnson was still very much in question.

February 11, 1932. A memo was sent to Inspector Eames in Rat River by his Assistant, Corporal Wild in Aklavik. Cpl. Wild reported that Captain ‘Wop’ May took off in his aircraft from Aklavik with new provisions for the pursuit teams but Captain May had to return due to poor weather. Eventually, the weather cleared sufficiently so that Captain May could fly and safely land at Rat River a couple of times to deposit the provisions.

After depositing loads of supplies at Rat River, Captain May intended to pick the supplies up again and fly them to Inspector Eames’ base camp. Cpl. Wild ended his memo by suggesting to Inspector Eames that he [Inspector Eames] return some of the RCMP search party to Aklavik as a fresh supply of RCMP were prepared to replace them.

February 17, 1932. A short message from Corporal Wild to Superintendent Acland in Edmonton, AB said; ‘Inspector Eames reports Johnson shot and killed by Police Party on Eagle River today. Staff Sergeant Hersey, Royal Canadian Signals member of party shot and seriously wounded by Johnson. Hersey is now in Hospital, Akalvik.’

February 18, 1932. A lengthy, four page detail report was compiled by the C.I.B. Office in Aklavik. Statements provided by all the members at the Inquest that followed shortly afterwards, provided details of the sequence of events between February 11th and February 17, 1932.

The remainder of the file consists of RCMP memos which talk about the sightings of Albert Johnson and describe the possessions, guns and ammunition found on his person. Albert Johnson used every possible trick to evade capture. He exhibited the signs of an expert marksman. He had super strength to climb high mountains which other men could not imitate.

His true identity is still not known, his actions were never understood. He killed one member of the Force and wounded two others. Fortunately, Constable King of the RCMP and Staff Sergeant Hersey, Royal Canadian Signals both recovered from their gun wounds. In the end, though, the violence perpetrated by Albert Johnson was visited upon himself and he, too, was killed.

An Inquest was held … ‘a man known as Albert Johnson came to his death from bullets fired by a police posse endeavouring to arrest the said Albert Johnson for the shooting of Constable King and Constable Millen of the RCMPolice from information received from Inspector A. N. Eames, Q.M. Sergeant R. F. Riddell and Constable A. W. King.’

A ‘Warrant to Bury’ was authorized by Dr. J. A. Urquhart to bury Albert Johnson on February 18, 1932.

Case Closed?

In this story, I have introduced several, very special members of the RCMP and I have described their role in the case. Constable Millen was shot and killed. Constable King and Staff Sergeant Hersey were seriously wounded. The story as I have presented it is brief. Many excellent books have been written on the topic and some suggestions for further reading are listed below.

The intrigue of this story prompts us to learn more about the personalities of each of the RCMP involved in this tragic event.

In Part IV, I will develop one personality among all those RCMP mentioned. He has garnered attention in the modern day for very, very mysterious reasons. On May 23rd, 2011, which is the 138th year Anniversary of the Force, then the name of our Mystery Man will be published. Then, the Mystery behind the Mystery Man can begin to be revealed.

J. J. Healy @Fort Healy

APRIL 23, 2011

This is the end of Part III

There are seven parts to this mystery series.

Part I : March 2011 - 'A Long Awaited Parcel Arrives'

Part II : April 2011 - 'Heroes in My Life'

Part III : May 2011 - 'Murder : No Small Matter'

Part IV : June 2011 - 'A Family Matter : A Well Kept Secret'

Part V : July 2011 - 0.209, A.N. Eames : 'Of Life and Lore'

Part VI : August 2011 - 0.209, A.N. Eames : 'Of Loss, Loneliness and Legacy'

Part VII : September 2011 - 'Preparations Underway for an Ottawa Memorial Service'