True and Fascinating Canadian History

RCMP Vet of the Month: March 2011

Part I: The Mad Trapper of Rat River:

A Long Awaited Parcel Arrives

RCMP Superintendent, (R'td)

This is a twofold mystery -- two minors mysteries merged into a major -- both interconnected and woven into Canadian history. I suggest readers prepare themselves by having a glass of cold water nearby in case one feels faint.

The first part of the mystery has its origin back many, many decades ago to the early 1930’s. It tapped all of Canada; from the far, frozen Arctic to the sunny deep south, from Canada's beautiful east coast to its majestic west coast. It had such an impact on Canada's history that it forever changed the RCMP and the course of Canadian policing. The second part of the mystery took place more recently in 2009.

This Magnificent, Monumental, Memorable Canadian Mystery is a story which I kept secret for a long time. Imagine -- a mystery so deep and bizarre that it would not be believed if the full story had been told prematurely! And yet, there’s a lesson for all police officers in the story often described as tragic and true.

Three rapid, sudden, sharp knocks made me sprint from the den to the front door of our Ottawa home. I was expecting a parcel from Air Canada. Over the years, the speed of my sprints has astonished my wife – in fact, she has calculated my speed from the den to the kitchen whenever lemon pie was mentioned. I have set records.

As I opened the door, I was surprised. The mail carrier was walking away in spite of my immediate response to his knocks. He had hurriedly left the porch. I caught him as he stepped on to the mail truck which was parked on the road. The parcel was very, very special to me and it had been long awaited. The parcel had traveled a long journey. It was delicate. It was a secret to only my wife and me.

To fully appreciate the importance and the significance of the parcel, its contents and its connection to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), I must begin my story with an unexpected event in my life which happened in May, 1971.

One day, I was working alone in the RCMP office in Charlottetown, PEI. A senior Officer suddenly burst into my office. He was unusually excited and he clutched a large brown envelope in his hands. The envelope contained the original report of a very, very celebrated RCMP case and it stretched back to the early 1930’s. Years ago, someone in the RCMP had once understood the historic value of this particular police file and had saved it from destruction. Someone had wanted to preserve its history.

Now, I was invited to peruse the entire original RCMP report from decades past -- it was the Arctic pursuit by the RCMP of ‘The Mad Trapper.’ It was a case which captured the imagination of Canadians and Americans in the early 1930’s. I was given the opportunity and the time to photocopy the entire file.

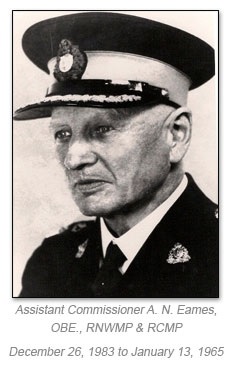

The Mad Trapper saga began on July 12, 1931. From RCMP Arctic HQ in Aklavik, Inspector A. N. Eames sent a memo to Constable E. ‘Spike’ Millen who was In Charge of the Red River Detachment. Eames wrote, “…it has been reported that a strange man going under the name of Johnson landed somewhere near Fort MacPherson on the evening of Thursday, July 9th, 1931.”

Inspector Eames said that Johnson arrived on a raft and that he owned very little kit but he had lots of money. Johnson had purchased supplies in MacPherson and he had enquired about the route into the Yukon. Constable Millen was asked by Inspector Eames to make enquiries about Johnson the next time Millen visited Fort MacPherson.

On September 11, 1931, Constable Millen replied to Inspector Eames. Constable Millen reported that he met a man who identified himself as Albert Johnson in Fort MacPherson. Albert Johnson told Millen that he had worked the previous summer and winter on the prairies and that he arrived at Fort MacPherson via the MacKenzie River.

Millen informed Johnson that if he intended to stay in the MacPherson area, that he would require a hunting licence which could be purchased at the Arctic Red River Detachment or in Aklavik. Johnson told Millen that he preferred to live alone in the bush and that he didn’t want to be bothered by other people. Constable Millen found Johnson to be evasive in his replies.

A few weeks later, Inspector Eames wrote a stern memo of concern to Constable Millen. Inspector Eames told Constable Millen that he [Eames] was surprised that he [Millen] had accepted Johnson’s excuse for being evasive about his travel plans. Inspector Eames explained that it was important for the RCMP to know the intended address of men coming into the north in the event there was an accident or if a person was reported as lost. Inspector Eames told Millen to, “… keep track of Johnson.”

Furthermore, Inspector Eames said that under suspicious circumstances or, if necessary, the RCMP has the right to search a person’s kit under the Games Regulations. Eames told Millen to instruct Johnson to communicate with the RCMP about his whereabouts as this was a common practice, “…after the death of Nicol and Beaman on the Gravel River.” Inspector Eames may have already perceived that Johnson was a suspicious character and perhaps worthy of police surveillance.

Ending his instructions, Inspector Eames said that if Johnson intended to travel to the Yukon, “... he should drop you (Constable Millen) a line acquainting the RCMP of his safe arrival as this help to the RCMP can prevent long police patrols which sometimes are unnecessary.”

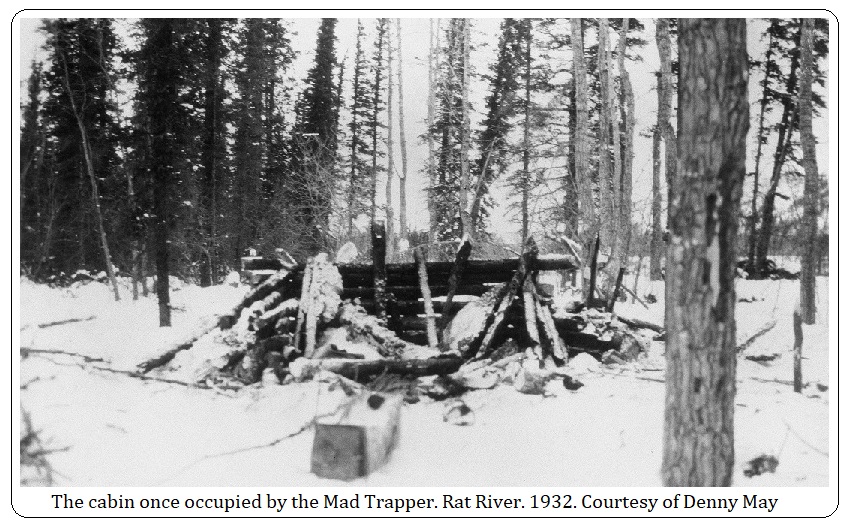

On January 2, 1932, Constable R. G. McDowell was instructed by Inspector Eames to interview Johnson at his cabin in the woods. Inspector Eames told McDowell that a complaint had been received of Johnson hunting without a game licence and of interfering with Indian trap lines. McDowell left Aklavik along with Constable A. W. King and two Special Constables. Johnson’s cabin was situated on the Rat River near Destruction City, so called after miners had perished on their way to the Yukon Gold Rush of 1898.

Constable McDowell and his posse reached Albert Johnson’s cabin late the following day.

McDowell approached Johnson’s cabin just as King knocked on Johnson’s door, at the same time shouting, “Are you there Mr. Johnson?” There was an immediate rifle shot through the door from inside the cabin. The bullet hit King who fell, then staggered into some nearby bushes.

McDowell too was nearly hit by rifle fire as he moved in King’s direction. The RCMP posse evaluated King’s bullet wound as being serious. Constable McDowell made the decision to immediately abandon an attack on Johnson’s cabin. Instead, the posse strapped King into a dog sled and raced towards Aklavik. The patrol travelled all night and twenty hours later, they reached Aklavik. King was admitted to All Saints Mission Hospital where he was attended by surgeon Dr. Urquhart. It was January 4, 1932.

Dr. Urquhart discovered that the bullet had entered two inches below Kings left nipple and exited in the same place on right side. Meanwhile, Eames decided to lead another posse to arrest Johnson but he could not leave Aklavik until the sled dogs were rested. Over a matter of a few days, a proposed interview of Albert Johnson had turned into a criminal matter. Johnson was now a wanted man for attempting to kill Constable King.

On January 12, 1932, Inspector Eames led a fresh posse to Johnson’s cabin. The posse consisted of Constables Millen and McDowell, two Interpreters plus three civilians and a guide. When Inspector Eames and his posse arrived at Johnson’s cabin they were fearful of an ambush. The area near Johnson’s cabin afforded little protection for the posse except for the banks of the Rat River. Johnson was commanded to leave the cabin by Eames but he refused. A decision was made to rush the cabin, but it was unsuccessful due to heavy fire from Johnson’s two automatic weapons. However, the door to his cabin was smashed in with rifle butts and a quick peek inside revealed that Johnson had dug into the cabin’s floor five feet below ground level.

Gunfire continued between Johnson and the RCMP for fifteen hours during which time Johnson had time to repair the cabin door and firmly close it.

At three o’clock the following morning, the posse used high explosives which blew in the door again and caused a gaping hole in the cabin’s roof. Another rush to the cabin by the posse failed. The posse had expected that Johnson would be stunned by the explosives but instead his gunfire was ever increasingly strong. Inspector Eames speculated that Johnson had found shelter from the explosives by extending the limits of space further under the cabin. By this time, supplies for the posse were depleted and provisions for the dogs were running low. Inspector Eames made the decision, once again, for the posse to return to Aklavik. This time, no one had been injured by gunfire but Johnson had evaded capture. They arrived in Aklavik on January 16, 1932.

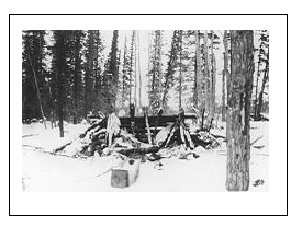

In his report, Inspector Eames said that he would be returning to Johnson’s cabin as soon as he could assemble a larger volunteer party. The next time, Eames said, a base camp would be established near the mouth of the Rat River. Early in the morning of January 20th, 1932, Inspector Eames left Aklavik again for the Rat River. When the posse arrive at the cabin, Johnson had already fled into the cold, expansive Arctic tundra. Now, there was an urgency to capture Johnson before he crossed the border into Alaska.

On January 31, 1932, Staff Sergeant Riddell of the Royal Canadian Signals and Constable Millen searched for Johnson in a wooded area when he suddenly fired on them. The pair returned fire, and they thought that Johnson might have been wounded or perhaps killed. For two hours it was quiet then the posse decided to slowly approach Johnson’s last known position in the woods. As Constable Millen got within twenty five yards of Johnson, he suddenly opened fire. Constable Millen was struck by a bullet and fell. He soon died in the Arctic snow. The sudden death of Constable Millen now turned Johnson into a killer, and Millen’s death likely caused the RCMP to wonder if Johnson’s days on this earth were few.

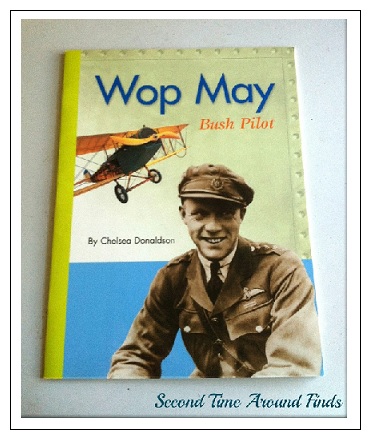

Meanwhile, Inspector Eames had recommended that an airplane be requisitioned from Edmonton, AB. with Captain Wop May as his preferred pilot. Wop May was a close and professional friend of Eames’.

Eames said the plane was necessary as a search party could not remain in the frozen temperatures too long without proper provisions for the police posse and the sled dogs. Soon, Wop May was in the air. After Wop May delivered food and blankets for the posse, Constable Millen’s body was transported out of the north by aircraft and then transferred by rail to Edmonton.

From Ottawa, RCMP Commissioner MacBrien told Inspector Eames, “... to take Johnson’s fingerprints after his capture whether dead or not and forward them by the quickest method.” Still, no one knew the true identity of the elusive outlaw labelled Albert Johnson by the American press. Nor did the RCMP originally expect Johnson to pose such a high risk or threat to their safety.

Wop May is credited with eventually spotting Johnson from the air, and radioing his position to the posse. Albert Johnson was cornered and he was offered no escape. But, he continued to shoot at the RCMP and to resist capture. Finally, on February 17, 1932, a short message to Edmonton RCMP Headquarters from Inspector Eames announced, “Johnson shot and killed by Police Party on Eagle River today. Staff Sergeant Hersey, Royal Canadian Signals member of party was shot and wounded by Johnson. Hersey is now in hospital, Aklavik.” A tragedy involving the RCMP and a mysterious, half crazed trapper had ended.

Eventually Hersey recovered from his gunshot wounds. The lesson for all police officers is the inherent danger attached to unexpected situations. Johnson’s violent actions towards the RCMP have never been understood, yet he killed one man and two other men were wounded.

A week after Johnson’s death, an inquest was held. Its concluding report said “… a man known as Albert Johnson came to his death from bullets fired by a police posse endeavouring to arrest the said Albert Johnson for the shooting of Constable King and Constable Millen of the RCM Police.”

A Warrant to Bury Albert Johnson was authorized by Dr. J. A. Urquhart. It was February 18, 1932.

With the aid of advanced scientific methods and increasing DNA matches, I hope one day that I will uncover Johnson’s true identity. Only then, will this page of the mystery be solved.

Reporting from Fort Healy,

J. J. Healy

March 23, 2011

Part I : March 2011: The Mad Trapper: A Long Awaited Parcel Arrives

Part II : April 2011 The Mad Trapper: RCMP then Inspector Alexander N. Eames

Part III : May 2011 The Mad Trapper: The RCMP National Memorial Cemetery Service

Part IV : The Mad Trapper Was Not a Canadian: Forensic Anthropologist