True and Fascinating Canadian History

Vet of the Month: November, 2021

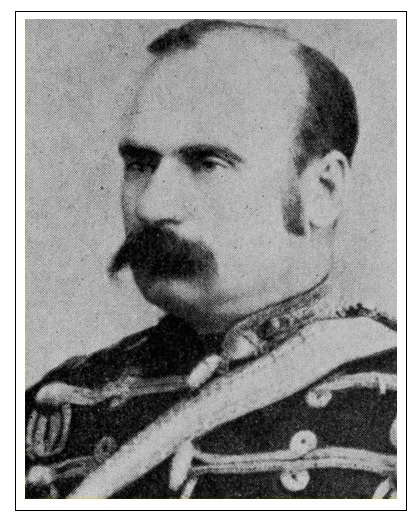

O.10, Assistant Commissioner Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier

RCMP Vets. Ottawa, ON

The early life of Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier is very detailed in Wikipedia. He was born on June 11, 1846 in Newry, Ireland, and his family emigrated to Canada and settled in Belleville, ON. While living in Belleville as a boy, Crozier worked in a number of odd jobs; a printing shop, as a clerk, and in a lawyer's office. For a short spell, he also studied at medical college. Crozier was fascinated by military life, and in 1862 he enlisted in the Militia. He was 16. Crozier served during the Fenian raids and over the next ten years he reached the rank of Major. After the formation of the NWMP was given Royal Assent on May 23, 1873, Crozier joined the NWMP on November 4, 1873. On account of his military background, he received a Commission at the rank of Sub-Inspector. (Wikipedia). Crozier is counted among the earliest Officers to join the NWMP, and his career was one marked by self-discipline and dedication. He held high aspirations, however, after several years of faithful service his career took a turn for the worse and in the end he lost the support of senior and influential Officers to become Commissioner.

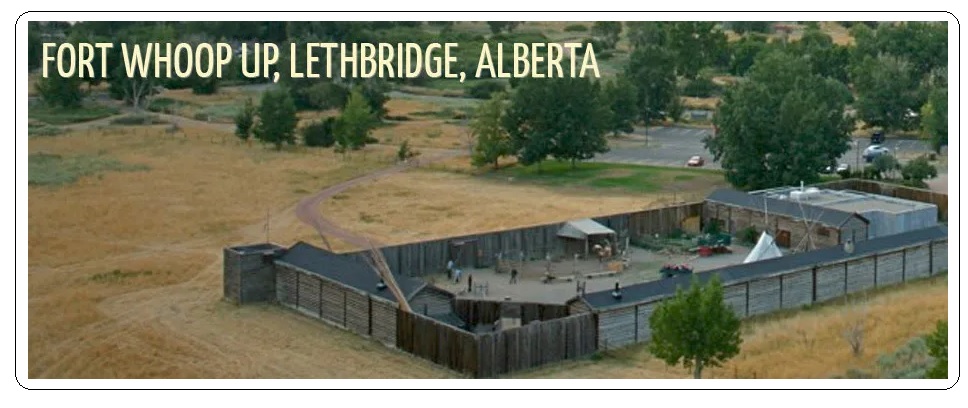

During the early planning stages for the March West, Commissioner French organized the NWMP into 6 mounted Divisions; A, B, C, D, E & F. An Inspector was appointed in charge of each Division. On July 7, 1874, the March departed Fort Dufferin in southern Manitoba with the various Divisions lined up in alphabetical order. Their destination was Fort Whoop-Up, the famous home of the notorious whiskey traders in present day Alberta. At first, Crozier was not given one of the more responsible posts in charge of a Division, but all that changed within a day or two after the March departed Fort Dufferin. Inspector Theodore Richer unexpectedly fell into disfavour with Commissioner G. A. French. In his very detailed book entitled, The North West Mounted Police 1873 to 1885, author Jack Dunn explained what transpired with Richer's setback and how the circumstances affected Crozier's career in a positive way. Dunn wrote, "Commissioner French placed Inspector Theodore Richer under arrest. Richer was charged with using insubordinate language while refusing to supply saddle horses for the wagon teams. He further threatened to notify Ottawa of what Richer claimed was the deplorable mismanagement of the Force." (Dunn: 97). It was critical that Commissioner French set an example and not allow Richer's infractions to go unpunished otherwise other NWMP would push discipline violations to their maximum limit. Hence, Commissioner French relegated Richer to a junior post, and Crozier was promoted as Officer In Charge of F Division. As the months went by, Crozier gained a reputation of reliance and dependability, and he was directly involved in one of the earliest interventions of the illicit whiskey trade.

After the March West had reached its destination in present day Alberta, one of its top priorities was to stamp out the illegal whiskey trade. One day, the NWMP was informed that William Bond, a whisky trader, was selling whisky from his cabin. Crozier was assigned to take a few men and to arrest Bond which he promptly did. Author Jack Dunn explained what transpired, "Five men were arrested when two wagons were discovered to carry whiskey. The patrol escorted these prisoners with three Indian women, three wagons of buffalo hides, and alcohol to Fort Macleod where Colonel James Macleod fined Bond and Harry Kamoose Taylor $200 each and three others $50 each." (Dunn: 161). In addition to the fines, the horses, the wagons and any exhibits which were linked to the offences were confiscated by the NWMP. Crozier was often called upon for more responsible assignments, and since he was reputed to possess a sensitive nature, some investigations left him disheartened.

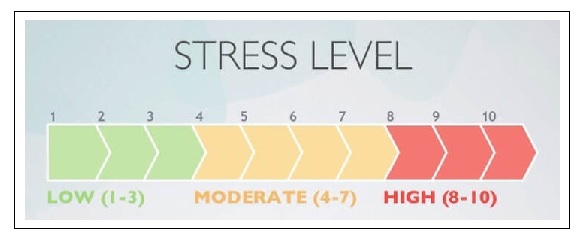

Throughout the March West and for several years afterwards, the stress on the NWMP never relinquished. Apart from a general malaise among the men, stress also led to desertions. Men who walked away, taxed by consequence, the physical demands of the men who remained with the NWMP to do the work. In 1875, it was discovered that several men had deserted from Fort Macleod. The investigation of the missing men was led by Crozier. Author Jack Dunn explained the unusual outcome of the file. Dunn wrote, "Superintendent Crozier led a police detail to overtake the deserters. On a hill, called Belly Butte, the deserters entrenched themselves and defied the police. Crozier was uncertain whether his men would support the use of force and withdrew, leaving the deserters to continue south. The loss of eighteen men only burdened the workload of the remaining troops." (Dunn: 173). The standoff was tense enough that it could have evolved into a loss of life. Crozier can be credited for evaluating it carefully. Meanwhile, living conditions at Fort Macleod were desperate as well as disheartening, and Crozier's mood was affected also. He and Macleod agreed that more defections were imminent if the quality of the food, warm uniforms and supplies were not soon improved. One constable reported conditions were so deplorable that the men were left to purchase their own clothes and warm blankets.

Crozier was reputed to be fair as well as a firm disciplinarian. He was among senior Officers who adjudicated in Service Court for discipline matters, and he could be tough. In one case a constable appeared before Crozier. He was charged for being, "absent from stables when watering order sounded, [and] using threatening language to [an] orderly. He was fined ten days pay and ten days confined to barracks." (Dunn: 352). After the case's disposition, the constable might have wished that a different judge other than Crozier had been chosen to sit. Crozier possessed sufficient inner strength to acknowledge he too had faults. Once, when assigned to Fort Macleod he experienced a near mutiny by the men. They claimed their workload was unbearable. The men sent their complaints to Sergeant Major Bradley, but he overlooked their objections and Crozier was forced to intervene. Author Jack Dunn reported, "Tedious arguments followed at an arranged meeting in the Orderly Room. Crozier admitted overlooking some issues and being ignorant of the existing conditions. Most requests were granted and the grievances eased." (Dunn: 355). The episode did not make Crosier look good in the eyes of his subordinates, and he was transferred to Fort Carleton. Shortly afterwards, the North West Rebellion of 1885 got underway, and one of its first battles at Duck Lake involved Crozier.

In late March, 1885, Crozier undertook a series of defensive measures to ensure the safety of Fort Carleton inhabitants which are detailed extensively in author Jack Dunn's book. Briefly, Crozier sent a search party under the command of Sergeant Alfred Stewart, four scouts and seventeen constables to retrieve goods seized at a store by supporters of Louis Riel. Near Duck Lake, a group of Metis led by Gabriel Dumont stopped the NWMP search party from their advance. The two opposing groups threatened each other face to face. Sergeant Stewart sent a dispatch rider back to inform Crozier, and after being appraised of the standoff, Crozier decided to organize a larger group of 100 men, 56 NWMP and 43 Prince Albert volunteers to confront the Metis. Crozier interpreted the clash between the NWMP and the Metis as a challenge to NWMP authority. The larger group led by Crozier met the Metis near the site of the first confrontation, and a battle soon broke out.

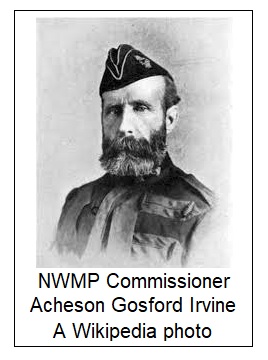

The aftermath of the skirmish was disastrous for both sides; on the Metis side, nine men were killed, and on Crozier's side twelve men died at the battle site, and of the twelve who were wounded, five more died. Among the dead were three NWMP; Constables Thomas James Gibson, George Garrett, and George P. Arnold. Later, Crozier came under severe criticism for his role in the battle. He argued that a show of force might have quelled any dissent and avoided any future bloodshed, but Commissioner A. G. Irvine was not even slightly convinced of Crozier's viewpoint. The Commissioner criticized Crozier for being too hasty and for coming too easily under the influence of the volunteers and others. (Dunn: 690-692). The Commissioner's assessment of Crozier's performance, plus earlier reports indicating that Crozier suffered from mental illness, dashed all hopes of him ever becoming a future Commissioner.

Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier was one of the earliest pioneers with the NWMP. He held a responsible position during the rigorous March West, and over subsequent years he tried to forge a favourable relationshp between the Indigenous Peoples and the NWMP. Unfortunately, Crozier's decision to confront the Metis at Duck Lake, and march into what appeared to be an ambush was controversial and his effectiveness as a leader came into question. Nonetheless, a week after the Duck Lake skirmish, he was promoted to Assistant Commissioner. In June, 1886 when he heard that the PM selected Lawrence William Herchmer for the Commissioner's job Crozier resigned. He died of a heart attack in Cushing, Oklahoma, USA on February 25th, 1901. He was 55. His body was returned to Belleville, ON where he was buried.

Reporting from Fort Healy,

J. J. Healy

November 23, 2021

Crozier, Leif Newry Fitzroy. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 December 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leif_Newry_Fitzroy_Crozier.

Dunn, Jack E. (2017). The North West Mounted Police 1873 to 1885. Jack E. Dunn Publisher. Calgary, AB.

Belleville Cemetery. Belleville, ON

Courtesy of Jack Hickman, Vets Kingston, ON & Jack O'Reilly. Vets. Toronto. ON.