True and Fascinating Canadian History

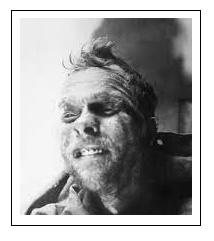

Shot and killed by Albert Johnson. Rat River, NWT. 1932

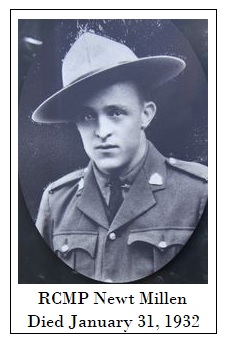

Case Overview of the Murder of RCMP Constable Newt Millen

And the Capture of the Mad Trapper

A 90th Year Anniversary: 1932 to 2022

RCMP Vets. Ottawa, ON

Read: rcmpgraves.com in The Ottawa Citizen: 2023

Within the wide spectrum of Canadian crime whether it was mayhem, mystery or murder, the identification of the Mad Trapper has never been solved, but nearly 90 years since his death in 1932, there is every hope and every possibility that new emerging technology with DNA will someday aid and reveal the fugitive’s true identity. In my view, the RCMP's file on the Mad Trapper has never been completely closed.

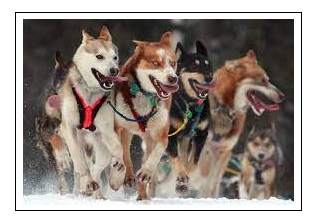

The Mad Trapper is a legend that Canadians have never forgotten, it is a chilling and suspenseful tale of a stranger in the North with a threatening gun. In his 1972 book entitled, Rat River Trapper, author Thomas Kelly wrote, "It is a true story of howling huskies, dangerous trails, and desolate tundra in a frozen world across which a fugitive flees before the oncoming posse." (p.1). Looking back, perhaps the RCMP underestimated the Mad Trapper's resolve to survive and escape? But who was the Mad Trapper, and what was the reason for his outward suspicion and obvious hatred of the RCMP such that would lead him to murder and evade capture? These questions have never been satisfactorily answered.

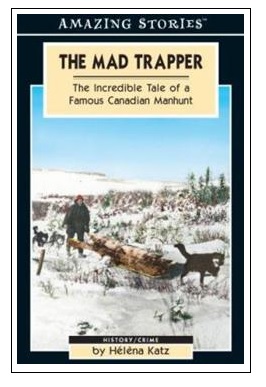

It is now time to review the murder case starting from the day when the Mad Trapper was first noticed in mid July, 1931 until the day of his death seven months later in mid February, 1932. In her book entitled: The Mad Trapper: The Incredible Tale of a Famous Canadian Manhunt, Canadian journalist and Université de Montréal criminology student Hélèna Katz provides a detailed day by day overview of the chase as well as a realistic glimpse into the eventual capture of the Mad Trapper by the RCMP and a dedicated troop of local volunteers. Author Hélèna Katz's book has been chosen to follow the incredible manhunt for the killer in freezing Arctic temperatures across Canada’s Northwest Territories and Yukon. So, why is the mystery of the Mad Trapper so fascinating, so important?

Impact on Canadian history

There are several reasons which make the criminal case of the Mad Trapper notable; first and most importantly, the case shone a light on the RCMP which has always acted in the North to protect Canada's sovereignty and this goal has consistently been a priority of the federal government, second, the tale is a valuable thread of Canada's history, its fabric and its folklore; third, the stranger was both a puzzle to the RCMP and a person of immense strength. He was a mysterious person possessed with well honed endurance skills fit for surviving in the North, and he had an unusual grit and determination to escape from the RCMP. Everyone questioned why?

From a general interest perspective, Canadian newspapers at the time (1931 to 1932) were filled with news about the RCMP's hunt for the fugitive, and some readers wondered whether or not the Mad Trapper could outpace and escape from the RCMP. Meanwhile, radios blasted the story into households all across Canada and the USA, and after several decades, no one has come forward to identify the killer. There are other considerations also.

Impact on RCMP history

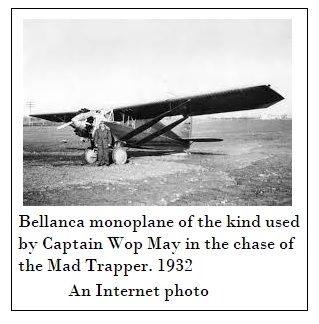

The tale of the Mad Trapper put the RCMP and its methods in the North front and center. The chase was the first time that an airplane was used in an RCMP manhunt and for surveillance purposes, second, the plane proved its worth to carry food, blankets, and medical supplies to the RCMP in emergency winter field conditions, third, it raised the need for the RCMP to create its own 'Air' Division which the RCMP did, and lastly, it was the first time that portable radios had been used in Canada for a police aerial search for an escapee. Without the valuable assistance of the airplane and its skillful pilot or the portable radios, the Mad Trapper would likely have evaded capture by crossing from Yukon into Alaska, and beyond the reach of the RCMP and Canadian justice. All the volunteers who assisted the RCMP must be recognized and praised, for without their constant dedication and bravery the Mad Trapper would never have been caught. In reality, the RCMP faced two huge challenges in the case of the Mad Trapper; the killer himself, who potentially could have assassinated any number of the RCMP pursuers along the escape route, and the fierce and dangerously cold weather which was also a factor which could not be downplayed. On any day, the sub Arctic temperatures could easily have taken the life of anyone in the RCMP team.

Significant dates in the case

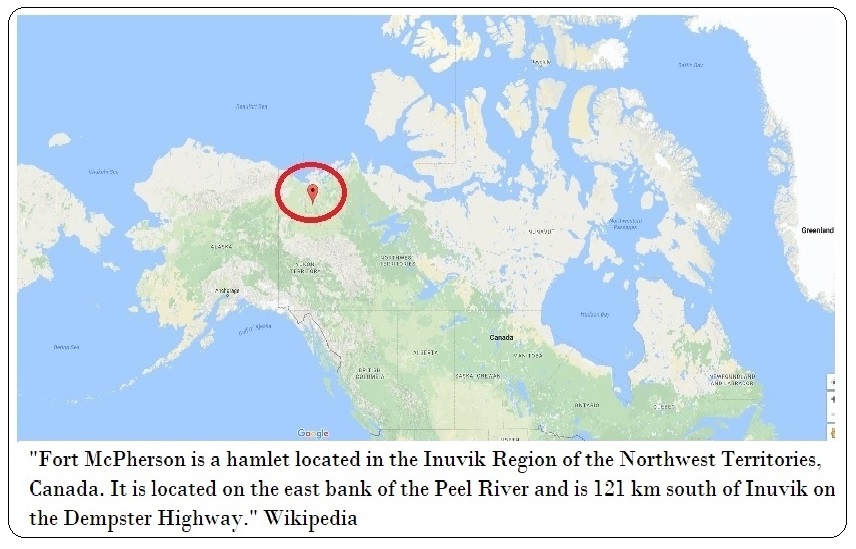

On July 9th, 1931, a male stranger arrived unexpectedly in Fort McPherson, located in the Northwest Territories a little north of the Arctic circle. Author Hélèna Katz described the stranger as, "About 5 feet 9 inches, and 175 pounds, he wasn’t a big man, but he had a sturdy build and his stooped shoulders looked like they had carried a heavy pack. He was about 35 to 40 years old," (Katz:15). Described as aloof and unfriendly, he was reputed to be an excellent sharpshooter, but his outward disposition was curt, gruff, mean and threatening. This unusual personality set the stranger apart from other people in the Fort McPherson area who were friendly and very hospitable to each other.

Meanwhile, Anglican Bishop W. A. Geddes was also visiting Fort McPherson. He had heard about the stranger, and when the Bishop returned to Aklavik he reported the stranger to RCMP Inspector Alexander Neville Eames, Officer Commanding of the Western Arctic. Soon, Inspector Eames contacted Constable Newt Millen at the Arctic Red River Detachment and instructed him to travel the 80 kilometers and interview the stranger in Fort McPherson. Leaving Red River, Constable Newt Millen arrived in Fort McPherson on July 20th, 1931 and on the following day he began a lookout in the hamlet for the stranger. It was not long before Constable Millen found him shopping in a supply store. For purchases, the stranger flashed a huge wad of $20 bills.

The stranger was reluctant to talk with Constable Millen, but he hesitantly identified himself as Albert Johnson. (Katz:22). It was the RCMP’s responsibility to determine if a newly arrived person could sustain themselves while living for the winter in the North? Constable Millen could have searched Johnson's gear under the Game Act, but he didn't, and this oversight brought sharp criticism upon Millen weeks later from Inspector Eames.

Constable Millen’s conversation with Johnson on July 21, 1931 was tense, and he barely responded to Millen's questions. Johnson said he spent the last winter (1930) on the Prairies and he had arrived in the North by heading down the Mackenzie. Millen caught Johnson in a lie, as Millen already knew that Johnson had floated down the Peel River on a homemade crude log raft.

In late July, 1931, Johnson bought a 12' canoe from a Gwich'in man, and paddled down the Peel River, but he got lost, and he had to back track towards Fort McPherson. He stopped at a small trading post where he met the owner Arthur Blake who incidentally was a former member of the RCMP. Blake gave Johnson directions to the Rat River which would eventually lead him to Yukon. (Katz:24)

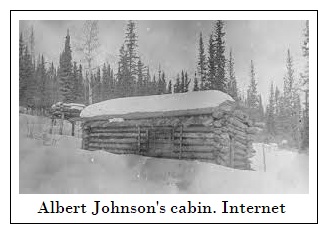

Not long after setting out a second time, Johnson feared that cold weather was about to close in, so he stopped paddling about 19 kilometers up the Rat River where he built a log cabin located about 65 kilometers north of Fort McPherson. He then began to set small game traps for food, but apparently that's not all that he did.

By December, 1931, Johnson had become the principle suspect in the tampering and disruption of native traps, so one hunter, William Nerysoo decided to report his complaints directly to the RCMP. He trekked 110 kilometers to the Red River Detachment where he met Constable Millen. Nerysoo identified Johnson as a suspect in the destruction of the natives trap lines. Something had to be done. It was December 25, 1931. (Kitz:30).

Constable Millen was the senior man at Red River Detachment, so he instructed Constable Alfred King and Special Constable Joseph Bernard to hook up the dog teams and to interview Albert Johnson, to determine if he was deserving of blame, and whether or not Johnson was in possession of a license to trap? Constable Millen's request for Constable King to visit Johnson seemed nothing out of the ordinary.

On December 26th, 1931, Constable King and Special Constable Bernard set out for the two day trek to interview Albert Johnson. The weather was frigid, so after 50 kilometers, the pair stopped overnight at Fort McPherson. The following day, they pointed the dogs down the Peel River. The route was exhausting so they stopped that night and camped at the mouth of the Rat River. They were 24 kilometers from Johnson's cabin. The pair slept. Under the stars, it was -34C. (Katz:31).

On the morning of December 28th, 1931, Constable King and Special Constable Bernard reached their destination. Smoke was rising from Johnson's cabin chimney. King announced himself, but there was only silence. He then explained that complaints had been received about someone interfering with the native's trap lines, and it was necessary for Johnson to be interviewed. Silence. King pounded on Johnson's door, but there was no response. At one point, King saw Johnson through the burlap sack covered window, but he refused to respond to King's request for a face to face interview. After several unsuccessful attempts to get Johnson's attention, Constable King decided to abandon any further action, and to trek the 130 kilometers to Aklavik where he could obtain a search warrant from Inspector Eames who was also designated a Territorial Justice of the Peace. They arrived in Aklavik on December 29th, 1931. (Katz:34).

Inspector Eames granted the Search Warrant for Johnson's cabin, and he instructed Constable Robert McDowell and Special Constable Lazarus to accompany Constable King and Special Constable Bernard on the second attempt to interview Albert Johnson. Eames had told the team to arm themselves with rifles in the event that Johnson resisted their attempt to search his cabin for evidence pertaining to the disruption of the natives traps. The team of four RCMP left Aklavik on December 30th, 1931, and they arrived at Johnson's cabin on December 31, 1931. (Katz:37). The RCMP expected some verbal opposition by Johnson, but they did not expect outright defiance or for shots to be fired against them.

RCMP Constable Alfred King shot and wounded

Constable McDowell and the two Special Constables remained nearby with the dog teams, while Constable King decided to approach Johnson's cabin alone. He stood to the side and shouted through Johnson's door that he had a Warrant to Search. Johnson answered with a rifle shot which hit King in the chest and he fell. He was still in Johnson's line of fire, and he had to seek cover and crawl away. (Katz:38).

Watching on, McDowell gasped when he realized that King had been hit, so he grabbed his rifle and began shooting as he sprinted to King lying near Johnson's cabin door. With McDowell's help, King was able to crawl to safety, but McDowell assessed King's wound and he decided that King would die of blood loss if the team did not get him to the hospital in Aklavik as soon as possible. McDowell pushed the team and the dogs to their limit and after mushing 20 hours in wind chilling -67C temperatures the RCMP arrived back in Aklavik. It was New Year's Day, 1932. (Katz:41) King underwent surgery. Johnson's rife shot missed King's heart by an inch. Albert Johnson was now a wanted man for attempted murder. Inspector Eames immediately began operational plans to arrest Johnson. He was determined not to fail. He surmised that he needed volunteers to assist the RCMP, but he needed bullet proof vests far more, but they didn't exist at the time.

Preparation to arrest Albert Johnson

New efforts to arrest Albert Johnson were immediately put into effect after Constable King had been shot and wounded. For reasons unknown, Johnson was determined to avoid the RCMP. He was considered very dangerous. Meanwhile, Eames had problems of his own; the dogs required adequate rest before they could travel again, finding volunteers would take time, and assembling supplies for the posse and the dogs also required purchasing and planning.

On January 3, 1932, Inspector Eames was prepared to depart Aklavik, and he would lead the posse himself; the team consisted of 8 men including RCMP and civilian volunteers plus 1 guide. (Katz:45). Johnson's cabin was 130 kilometers away. Forty-two dogs carried supplies, and two days later, the posse was joined at Arthur Blake's Husky River Trading Post by Constable Millen and volunteer Charlie Rat. In addition to food and supplies, Inspector Eames also purchased 20 pounds of dynamite from Arthur Blake in case it was required to dislodge Johnson from his cabin. (Katz:46).

On January 6th, 1932, the team lead by Inspector Eames left Arthur Blake's Husky River Trading Post, but enroute Guide Charlie Rat got the team lost, and they wasted one day's valuable time. It was January 7th, 1932. They were no closer to their goal, and already, dog food was running low. The posse didn't arrive at the vicinity of Johnson's cabin until the night of January 8th, 1932, and only on the following day were they prepared to take action against Johnson who was still holed up in his cabin. Johnson was waiting for them. He immediately began rapid firing on them. (Katz:49).

From the beginning the RCMP was disadvantaged. It was January 9th, 1932. The weather hovered around -42C, the team was exposed to the openness of the landscape, and the wind, and they had had little rest or sleep. Food, water and warmth were a constant concern. The dogs required nearly full time attention. Meanwhile, Johnson was relatively warm and secure in his cabin. Every effort to negotiate was dismissed. As day turned to night, the RCMP team was desperate, but the weather was worse. Perspiration caused the interior of their clothes to freeze.

At around midnight on January 9th, 1932, Inspector Eames decided to use the dynamite as a last resort, but he discovered that it was frozen, so they placed the dynamite close to their bodies to sufficiently warm it. The tactic worked, but, due to Johnson's firepower, the RCMP could not get close enough to make an effective strike with the dynamite, and various attempts to lob single sticks of dynamite at the cabin only bounced off and lost their effectiveness.

On January 10th, 1932, Inspector Eames made one final attempt -- he taped a few pieces of dynamite together and under the cover of complete darkness, Eames lobbed the dynamite on top of Johnson's cabin. The roof was blown off, and a wall was partly caved in, but the explosion had no effect on dislodging Johnson. (Katz:52). Johnson continued to shoot blindly in the direction of the RCMP team. Inspector Eames knew he had to abandon any further action. After a fifteen hour police operation to arrest Albert Johnson, this phase came to an end. Twenty pounds of dynamite had been used, and over 700 rounds of ammunition had been expended but to no avail. The RCMP had to mush back to Aklavik safely. The RCMP team arrived in Aklavik on January 12th, 1932. A new operational plan was required. The manhunt was not over, but Johnson had won the last round.

On January 14th, 1932, Inspector Eames instructed Constable Millen and Trapper Karl Gardlund to set up surveillance on Johnson's cabin, but a fierce storm caused them a delay while they were in the bush and when they arrived on January 16th, 1932 Johnson was gone. He had taken advantage of the same storm that had delayed Millen and Gardlund. Johnson had abandoned the cabin and had escaped. (Katz:56).

In the meantime, Inspector Eames worked feverishly to muster volunteers, he received permission from the Department of National Defence to recruit Radio Operators Quartermaster Frank Riddell, and Staff Sergeant Earl Hersey. Up until this time, portable radios had never been used under extreme Arctic outdoors weather conditions, but Eames was anxious to assemble the new team and be back on Johnson's trail as soon as possible. He feared that Johnson might escape into Alaska, USA which would only complicate Johnson's arrest and confound the entire criminal justice system.

Finally, the new RCMP team under Inspector Eames was prepared for action. They departed Aklavik on January 16th, 1932, and two days later they arrived at the mouth of the Rat River to search for Albert Johnson. They searched the Rat River Canyon but there were no sightings of Johnson, and it was impossible to predict where he might be hiding. (Katz:61). The cold weather was the team's constant enemy, and the landscape was covered with obstacles; canyons, hills, thick bush and deep streams.

These obstructions inhibited the team's effectiveness, but Inspector Eames' main concern was an unexpected sniper attack on the team by Johnson. Continuous searching was ineffective, and by January 21st, 1932, Inspector Eames was forced to reevaluate. Food was getting low, so he was forced to cut back on the number of volunteers on the team. (Katz:64). By January 23rd, 1932, some of Eames' team returned to Aklavik, and some men including Constable Millen stayed behind to continue searching. Millen was the only RCMP who could positively identify Johnson if they caught him.

In Aklavik, a new plan of attack was required. Eames knew that Johnson was on the move. He had the uncanny ability to stay ahead of the posse. The story was making headlines in newspapers and radio around the country, and a news reporter in Aklavik labeled Johnson as the 'Mad Trapper.' His reputation as a stealth escapee spread across North America. Johnson was also well armed. His first victim, Constable King was recovering from a chest wound in Aklavik and there was every potential that Johnson might shoot another RCMP. The stakes were high. Inspector Eames had to located Johnson, and arrest him.

In the meantime, Constable Millen, and volunteers Gardlund, Verville and Quartermaster Riddell circled around to search Johnson's cabin again in the event he had returned to fetch supplies. (Katz:66). The Millen team had been in the field for two weeks, they were cold and hungry. The temperature was -44C. Eventually, the posse found tracks not far from Johnson's cabin and not far from where the Rat and the Bear River meet. They continued tracking. It was January 28th, 1932, and Constable Millen was desperate too. They had run out of dog food. (Katz:68). They were also afraid of an ambush. At the same time, Johnson was now within reach of the divide between the North West Territories and Yukon.

Constable Millen and the volunteers had lost Johnson's trail, when unexpectedly a Gwich'in man who had once been a member of the search team approached to say that he had heard two rifle shots in the distance. The search party retraced their path, and they soon saw the distinctive markings of Johnson's snowshoes. Johnson had backtracked from the open landscape to the rocky terrain of the Richardson foothills (Kitz: 70). The posse split up -- Millen and Gardlund searched together while Verville and Riddell stayed together. Soon, they found a dead caribou that Johnson had killed, and soon afterwards Verville and Riddell also spotted a faint wisp of smoke in the distance. It must be Johnson. (Katz:761). It was to late in the day. The foursome decided to rest and arrest Johnson the following day. The air had an ominous sense. It was January 30th, 1932.

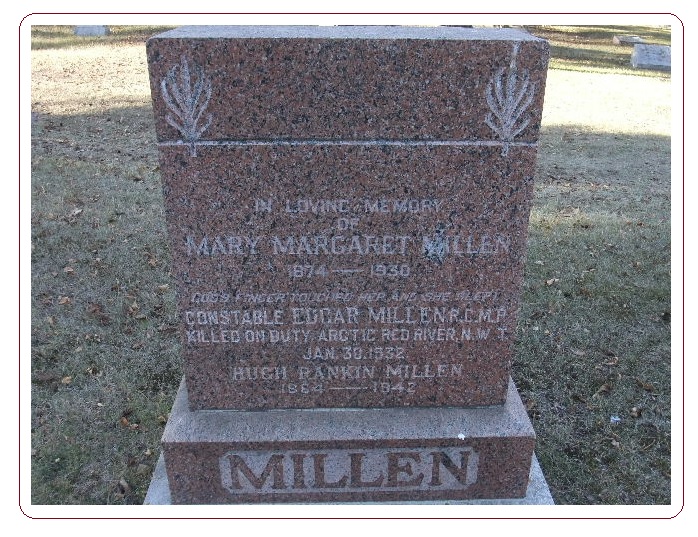

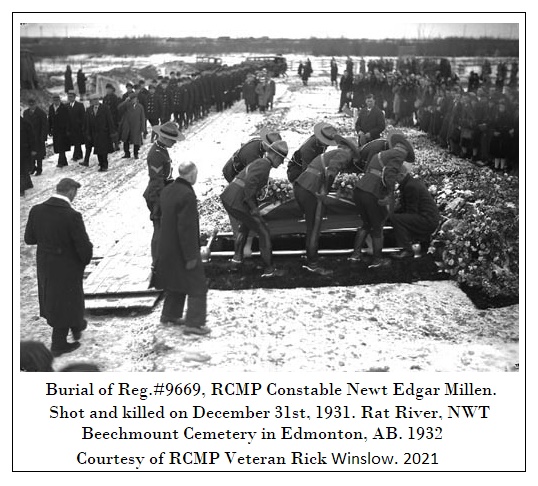

Constable Newt Millen is shot and killed

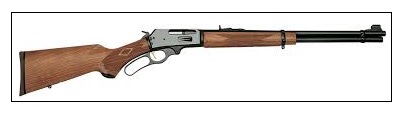

The next day on January 31, 1932 it was -38C. Constable Millen and his team of three volunteers cautiously tracked Johnson about eight kilometers and approached the area where they had seen the smoke the previous night. They decided to spilt up again in two's, and unexpectedly Johnson spotted them and shot in their direction. He was armed with a .30/30 rifle and he continued to fire. They lost sight of Johnson, but they continued to fire in his direction hoping to land a shot and wound him. Then there was complete silence. Finally, Constable Millen broke the silence. He shouted for Johnson to give himself up, but there was no response. (Kitz:73). The situation was eerie.

After two hours of laying motionless, the team decided to regroup. They decided to move cautiously, and to close in on Johnson. They intended to make his escape impossible. Volunteers Verville and Gardlund approached from one direction while Constable Millen and Quartermaster Riddell moved up to higher ground. They spotted Johnson. He didn't move. Constable Millen fired once, and Johnson returned fire. Millen shot once again, and Johnson replied with two shots. Johnson then shot a third time, and the bullet hit Constable Millen. He turned and fell face down in the snow. The bullet had hit his heart. He was dead. It was January 30th, 1932. Constable Millen had served in the RCMP faithfully for eleven years. He was 30 years of age. (Katz:75).

The three remaining volunteers (Verville, Gardlund and Riddell) kept Johnson pinned down with rifle fire while they moved Constable Millen's body out of Johnson's view. They were about 50 kilometers from where the Rat River flows into the McKenzie. It was decided that Quartermaster Riddell would mush back to Aklavik and report Constable Millen's death to Inspector Eames. On his way to Aklavik, Riddell was met by Canadian Forces Staff Sergeant Frank Hersey and Special Constable Sittichinli. They were told about Constable Millen's death by Sergeant Riddell.

After a few hours, Hersey and Sittichinli met up with volunteers Gardlund and Verville -- Gardlund and Verville had already built a crude platform upon which they hoisted Constable Millen's body for protection from wild animals. Hersey, Sittichinli, Gardlund and Verville decided to return to Aklavik, and after they departed, Johnson walked over to see Constable Millen's body. Then Johnson climbed a nearby vertical cliff with an ice axe, covered his tracks and disappeared into the dark and freezing Arctic cold once again.

Volunteers Verville, Gardlund Hersey and Special Constable Sittichinli arrived back in Aklavik on January 31st, 1932. After Constable Millen's death, the manhunt for Albert Johnson soon became a national story, and the search for the Mad Trapper of Rat River gained a new intensity. Inspector Eames faced several unusual factors; Johnson's incredible stamina and his wilderness skills, the large scale geography to search, the unlimited places that Johnson could hide, the extreme weather conditions, and the stress placed on the RCMP to quickly capture Johnson.

Meanwhile, there was increased tension in the North. Everyone was on edge -- residents feared that Johnson's stealth could allow him sneak into any village to murder innocent victims, and the RCMP was worried that Johnson might escape over the Richardson Mountains and into northern Yukon. (Katz:80). If there was any hope to capture Johnson, Inspector Eames concluded that an airplane was required, but an airplane had never been used in a manhunt in Canada, the snow was deep, and there was a lack of suitable take off and landing areas for an airplane. (Katz:83).

While Ottawa considered the RCMP's request for an airplane, and its cost, Inspector Eames set out again to arrest Albert Johnson. It was February 2nd, 1932. This time, he was accompanied by volunteer Sergeant Riddell, Special Constable Sittichinli, former RCMP Constable Constant Ethier, and two trappers Ernest Maring and Peter Strandberg. The search party was met at Fort McPherson by Knut Lang and Frank Carmichael. At Rat River, they were joined by former RCMP Constable Arthur Blake, August Tardiff and John Greenland. Constable Sid May, and Special Constable Moses joined the posse from Old Crow Detachment. The posse grew to 17 men, and they were determined to return to Aklavik with Johnson dead of alive. (Katz:85)

On February 2, 1932, Inspector Eames was informed that an airplane was approved, and it's pilot was the famous WWI superstar Captain Wilfred 'Wop' May who was living in Fort McMurray, AB. Wop May departed Edmonton for the North and the manhunt over 2900 kilometers away.

By the time the posse reached the location where Constable Millen had been killed it was February 5th, 1932. The posse searched Johnson's former camp for clues -- no blood was found which indicated that Johnson had not been hit or injured earlier in the shoot out with Constable Millen. The posse decided to fan out and follow faint tracks made in the snow by Johnson.

The posse chased Johnson over February 6th, 7th, and 8th, 1932. They discovered that during the night, Johnson retraced his steps in an attempt to confuse the posse. Inspector Eames was convinced that Johnson was heading for the Richardson Mountains, and from there he was within range of reaching Yukon. If Johnson's luck held out he could escape from Yukon then cross the US Canadian border and into Alaska.

Captain Wop May was in the air and anxious to reach the manhunt. His flying skills were tested to the absolute limit. He once recalled that part of the trip was the worse that he had ever experienced, he said, "We bucked snowstorms and terrific north winds all the way down the river. Near Fort Norman, at four thousand feet, the wind had increased to hurricane force. Although at times, I had my throttle wide open, we were being blown backwards over the ground, and then a blizzard blotted out the earth and left us bumping about up there completely blind." (Katz:94). It was widely speculated among pilots of the day that anyone with less than Captain May's skills in the air would most certainly have met with disaster and possible death.

Captain May arrived in Aklavik on February 6th, 1932. It was storming so he decided to stay overnight. The next day, he met Doctor J. A. Urquhart who decided to join the posse in the event there were more causalities in the field. On February 7th, 1932, Captain May and Doctor Urquhart took off. The posse was eventually located at the mouth of the Rat and Husky River. Later in the day, Captain May flew over the area, and he spotted Johnson's tracks in the snow, but the fugitive was fast and evasive.

The next day, it was decided that Dr. Urquhart would return by air to Aklavik where his medical expertise was required. The return trip to Aklavik was also an opportunity for Captain May to fill the plane with fresh supplies including blankets and fresh food for the dogs. On February 8th, 1932, Captain May delivered valuable supplies to the posse, and this strategy allowed the posse to concentrate solely on capturing Johnson. (Katz:97).

With the help of Quartermaster Riddell in the plane as a spotter, Captain May took to the air again. They saw Johnson's tracks, but some had been blown over while others were clear. At one point, it was obvious that Johnson had followed a creek and he had reached the Barrier River. Then he headed back to a continental divide that splits the North West Territories from Yukon. Johnson had then climbed to a high ridge from where he could survey the area from a great distance. The RCMP realized that Johnson was continuously watching the posse's movements and their location. In consultation with Captain May, Inspector Eames decided to move his men ever closer to where Johnson's tracks had last been seen from the air. Captain May and his airplane proved to be miraculous help. (Katz:98).

The next day, Captain May decided to return to Aklavik. On his way, he landed where Constable Millen had been shot a week earlier. Constable Millen's body was loaded into the plane. Captain May returned to Aklavik where Constable Millen's body was stored in the RCMP Guardroom until it could be flown to Edmonton for his funeral. Captain May was grounded in Aklavik due to storms and high winds. On February 11th, 1932, major newspapers in Canadian cities reported that the chase for the Mad Trapper might be coming to an end.

In the meantime, Captain May had loaded more fresh supplies onto the plane and delivered them to the searchers in the field. On February 12th, 1932, Captain May flew several miles over the search area. It was estimated that Johnson was two days ahead of the posse, so Inspector Eames decided to send some men over the Richardson Mountains and into Yukon. (Katz:102). The posses was astounded at Johnson's ability to outdistance them. At one point, he had traveled in snowshoes over 145 kilometers in three days.

Somehow impossible, Johnson had climbed the impassable Richardson Mountains during high winds and low temperature. It was an incredible feat for anyone, but by this time, Johnson was probably exhausted, hungry and weak. As well, he was also carrying his own supplies over his shoulders. Johnson's strength seemed superhuman. (Katz:104).

On February 13th, 1932, Captain May made another trip to Aklavik for supplies accompanied by Inspector Eames. Later, they flew on to La Pierre House, Yukon. By this time, there was no doubt in Inspector's Eames' mind that Johnson had reached Yukon probably by crossing though the Barrier River Pass. Considering the distances that he traveled, Johnson had proven that he was a first class bushman. In a speech once given in Calgary, Captain May recalled, "His tracks could be seen in one place tonight, then tomorrow morning then they would be seen 20 or 30 miles away. He traveled that distance in one night." (Katz:105). Even to native bushmen in the North, Johnson's feats were unthinkable.

On February 14, 1932, Captain May left La Prairie House and was in the air once again. He searched for Johnson's track, but poor weather conditions forced him to land the airplane and wait out the storm. On the following day, the posse that Eames had instructed days earlier to travel by dog team from the North West Territories arrived. They too joined the posse at La Prairie House, Yukon.

By this time, Inspector Eames, volunteers Riddell, Carter and Gardlund had set out on foot to renew the search for Johnson. They discovered his tracks mingled among caribou tracks. It had been a month since Johnson had fled his cabin, and the posse seemed to detect that Johnson was growing increasingly weak. In places, his tracks zigzagged, and the posse knew he had no food. The cold and poor weather, a lack of food and energy and diminished time were all against Johnson. Not far away, a posse was determined was to capture him. (Katz:107). It Johnson had ever wanted to surrender, he reckoned that his chance to be taken alive had also passed him by. He pushed on. In Johnson's mind, he only had hours to live.

The posse was tired too. That night they stopped and set up camp at the mouth of the Eagle River. Johnson had eluded the RCMP for seven weeks. They knew the end of the trail was close. It was February 16th, 1932. (Katz:107)

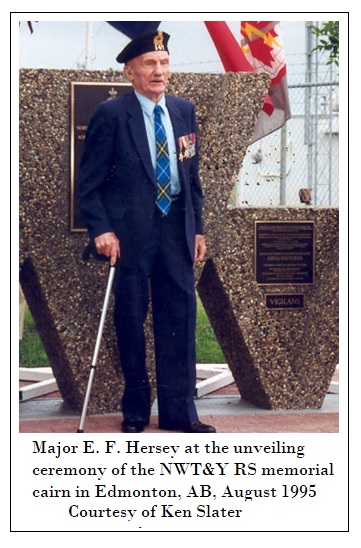

The posse was awake early on February 17th, 1932. Captain May and his plane had been delayed at La Prairie House due to fog. Around noon, the posse found Johnson's tracks near the Eagle River. They could tell he had climbed a tree to spot the posse and to determine an escape route. At the same time, volunteer Canadian Forces Staff Sergeant Hersey unexpectedly saw a man only 270 meters away. Hersey was taken by surprise as he had never seen Johnson, but Hersey recognized Johnson's snowshoes. Johnson had tried to backtrack, and had not realized that the posse was so close by.

Canadian Forces Staff Sergeant Frank Hersey shot and wounded

The posse had decided that Johnson was to be taken into custody alive. However, while Johnson was climbing an embankment, Staff Sergeant Hersey knelt down to get a good shot at the fugitive before he could escape again. Unexpectedly, Johnson turned and fired at Hersey, who was hit in his kneecap. The bullet from Johnson's .30/30 rifle then entered Hersey's elbow and he collapsed. (Katz:111). Hersey didn't lose consciousness, so he burrowed into the snow and out of Johnson's sight. Within minutes, the remainder of the posse had rounded the bend in the Eagle River and was at the site where Johnson had last been seen. The posse spread out in all directions.

From their vantage point in the middle of the frozen Eagle River, Inspector Eames and Constable May called out to Johnson to surrender, but he ignored them and continued to shoot at his pursuers. Eames shouted to him again, but he continued to shoot. There was no where that Johnson could go. He was surrounded.

Albert Johnson warned to surrender. Killed.

Johnson finally laid down and burrowed into the soft snow. He used his back pack to shield himself. The strategy was of little protection, and he already was hurt. A bullet from the posse had hit a box of ammunition in Johnson's pocket and blown a hole in his leg. He was loosing blood. Over a period of ten more minutes, and in spite of more warning to surrender, additional rifle shots from the posse hit Johnson in his shoulder and his side. The posse tried to injure him, but not kill him. But by this time, Johnson was dead. It was February 17th, 1932.

Captain May arrived overhead in the airplane and saw Johnson's body from the air. He motioned to the posse that Johnson was lying in the middle of the Eagle River. He was still and lifeless. Johnson had made it to within 270 kilometers from the Alaskan border. For him, Alaska was freedom. Albert Johnson, the so called Mad Trapper of Rat River had resisted arrest to the very end. (Katz:115). Johnson's body was flown back to Aklavik where he was buried.

Motive to violence and mental health assessment

Over seven weeks, it had taken ten RCMP including three Special Constables, and more than thirty civilian volunteers to capture Johnson, and in the midst of the chase, he had wounded Constable King, shot and killed Constable Millen, and shot and wounded Canadian Forces Staff Sergeant Hersey. Each of those incidents were crimes which cannot be overlooked and for which he was the sole suspect.

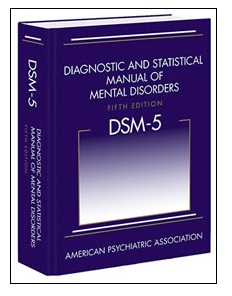

However, after the whole investigation, one is left with questions about Johnson's motives, and whether or not he was fully responsible for his actions? It is only fair to ask. In 1932 and at the time Johnson was fleeing from the RCMP, it seemed that he was intent to kill and to escape, but today with significant advances in neuroscience and psychiatric research might it also be discovered that Johnson was in crisis and in desperate need of mental health treatment? This thought is purely conjecture. One could argue that the same mental health assessment might apply also to many other people living solitary lives at that time in the North, but interestingly Johnson was the only person known to have gone berserk at the time.

The Berserker / Blind Rage Syndrome

From everything that has been written and observed about Albert Johnson, and the fact that that he apparently went berserk makes his case somewhat unique, and worthy of rethinking. The following scientific research may shed some light on Albert Johnson's possible mental state, and his deliberate avoidance of the RCMP.

As recent as 1987, a proposal was submitted by forensic psychologist Armando Simon to incorporate "The Berserker / Blind Rage Syndrome" as a potential new diagnostic category for the DSM-III. According to Simon, "The Berserker/Blind Rage Syndrome is characterized by, (a) violent overreaction to physical, verbal, or visual insult, (b) amnesia during the actual period of violence, (c) abnormally great strength, and (d) specifically target-oriented violence." Simon's study was abbreviated in an academic abstract in which he drew parallels between the four characteristics he identified and between Viking Berserkers of the Middle Ages. Some of Simon's characteristics seem to apply also to Albert Johnson. Perhaps Simon's study with berserkers of long ago has some connection, even remotely, to the mysterious life, motives, and mental state of Albert Johnson?

One may never learn the answer to these particular questions as they pertain to Johnson, but imagine how crimes of all sorts might be significantly reduced if mental illness was diagnosed early on and more help (medicine, talk therapy and critical care) was offered to people who suffer from mental illness? In theory, the Albert Johnson episode might have been prevented.

The Mad Trapper affair ended as it began -- a mystery.

in the Chase and Capture of The Mad Trapper

(Other names will be added as they become known)

This segment is dedicated to the RCMP Posse involved in the Arctic chase and the eventual capture and death of the Mad Trapper on February 17th, 1932; the members of the team are:

Special Constable Joe Bernard. His place of burial is not yet known.

Reg.#10186, William Sharples Carter died on September 17th, 1991. He was buried at 'Depot'

Canadian Forces Major Frank Hersey was shot and wounded by the Mad Trapper. Major Hersey died at the age of 101 in 2006. He was buried in Union Cemetery, Barrie, ON.

Reg.#10211, Alfred Wheldon 'Buns' King died at the age of 72 in 1978. He was buried in Hillcrest Cemetery, Petrolia, ON.

Reg.#10269, Robert G. McDowell died at the age of 95in 2003. He was buried in Oliver, BC.

Reg.#9669, Newt Edgar Millen was shot and killed in 1932 by the Mad Trapper at the age of 31. He was buried in Beechmount Cemetery in Edmonton, AB.

Special Constable Lazarus Sittichinlis died in 1988 at the age of 98. He was buried in Aklavik NWT.

Reg.#7536, Corporal Richard Samuel Wild died in 1978 at the age of 86. He was cremated in North Vancouver, BC

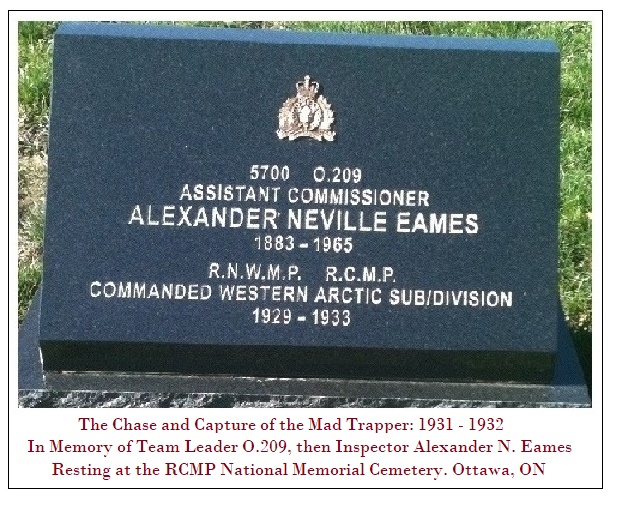

RCMP Team Leader, O.209, Inspector Alexander Neville Eames retired as an Assistant Commissioner while the Commanding Officer (CO) of Nova Scotia in 1946.

Mr. Eames died in North Vancouver, BC in 1965 at the age of 82. He was then cremated at Ocean View Cemetery in Burnaby, BC., in 1965 but his remains were not discovered until 2011 at which time I 'adopted' him.

His remains were flown to me in Ottawa, and he was buried in the RCMP National Memorial Cemetery at Beechwood, Ottawa, ON.

A photo of Assistant Commissioner Alexander Neville Eames' RCMP grave stone at the RCMP Memorial Cemetery can be seen below.

xMay they all Rest in Peace.

(Click on Part I, II, III or IV)

Part I : The Mad Trapper: A Long Awaited Parcel Arrives

Part II : The Mad Trapper: RCMP then Inspector Alexander Neville Eames

Part III : The Mad Trapper: The RCMP National Memorial Cemetery Service

Part IV : The Mad Trapper Was Not a Canadian : Forensic Anthropologist

Anderson, F. W. and Downs, Art. (1986). The Death of Albert Johnson: Mad Trapper of Rat River. Heritage House Co. Surrey, BC.

Katz, Hélèna. (2004). The Mad Trapper: The Incredible Tale of a Famous Canadian Manhunt. Altitude Publishing Canada. Canmore, AB.

Kelly, Thomas P. (1972). Rat River Trapper. Paper Jacks: General Publishing Co. Ltd. Don Mills, ON.

North, Dick. (1972). The Mad Trapper of Rat River. The Alger Press: MacMillan of Canada. Toronto, ON.

Smith, Barbara. (2009). The Mad Trapper: Unearthing a Mystery. Heritage House Publishing Co., Surrey, BC.

Wiebe, Rudy. (1980). The Mad Trapper. Red Deer Press: A Fitzhenry and Whiteside Co.

Simon, Armando. (1987). The Berserker/Blind Rage Syndrome as a Potentially New Diagnostic Category for the

DSM-III. Source: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2466/pr0.1987.60.1.131.