True and Fascinating Canadian History

Vet of the Month: August, 2016

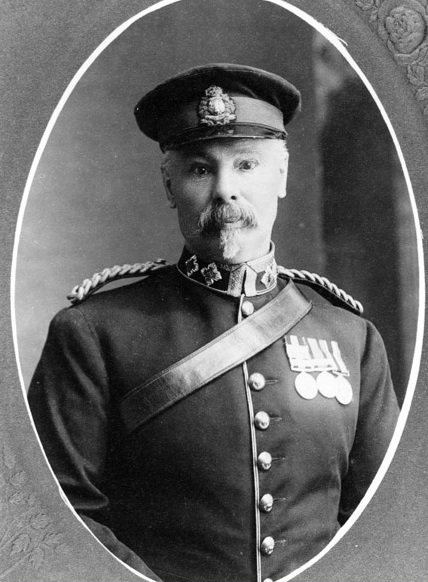

O.79, Superintendent Charles Constantine

RCMP Vets. Ottawa, ON

The word 'fever' may be the only suitable word which adequately sums up the rush for gold by thousands of men and women migrating to the Klondike in northwest Canada and pegged just east of the Alaskan border beginning around 1897.

Up until that time, no other event but the gold rush, had such a direct influence on Canadian cities and towns as did the huge throngs of people destined for the Klondike. The buzz created by a gold strike was far beyond anyone's expectations including the North West Mounted Police (NWMP).

In his famous book Klondike (1972), Canadian author Pierre Berton reported on the impact of the gold rush. Berton wrote, "Suddenly, in 1897, the news from the Klondike burst upon the continent and everything was changed ... For the first time, really, the Canadian north was seen to be something more than frozen wasteland ... Every western Canadian community from Winnipeg to Victoria was affected permanently by the boom ... Vancouver doubled in size almost overnight; Edmonton's population tripled." (p.xi). As a police force still in its infancy, the NWMP was on the scene early to witness the wide open bubble burst of migrants and the accompanying bustle. The perfect timing was true for the NWMP'spresence in western Canada as well as in the Yukon.

To a large extent, the legend of the Mounties grew out of the peaceful settlement of the Canadian west -- the success of the March West and the name Superintendent Sam Steele, in particular come to mind. While the Canadian Pacific Railway was under construction, hundreds of Americans flooded into the prairies looking for work. Whenever trouble broke out, it was the Mounties who peacefully maintained law and order. So, it was quite natural for the NWMP to equate their experience in western Canada to the challenging call of the Yukon. If peace was possible in one place why not expect it to take hold in another?

The Mounties trail to the Yukon began this way. At one time, Johnny Healy an American entrepreneur, had established Fort Whoop Up, a profitable whiskey trading post near today's Lethbridge, AB. According to Wikipedia, Healy sold the Fort just one step ahead of the inbound Mounties then he headed north to operate a transportation company in the Klondike. But, Healy ran into thick trouble when, according to Pierre Berton, some vengeful miners intended to lynch him so he called upon a couple of Mounties to enter the Klondike region and to care for his personal protection. (xvi).

As luck would have it, and partly because of Johnny Healy's predicament with the miners, the Mounties found themselves well situated in the Yukon before the gold rush. And, among all the NWMP called to the Yukon, one Mounted Police Officer stood out in the mind of NWMP Commissioner LawrenceHerchmer -- it was Superintendent Charles Constantine -- a Canadian of note and a name very worthy for Vet of the Month.

Charles Constantine had an illustrious career as a military officer as well as an Officer in the NWMP. He was born in 1849 in Bradford, Yorkshire, England, and he immigrated to Canada with his familyat the age of five. In 1870, he joined the Red River Expedition with the 2nd Quebec Battalion of Rifles and he took part in the Red River Rebellion again Louis Riel with the Winnipeg Light Infantry. Later, he was appointed Chief of the Manitoba Provincial Police (MPP), and after the Rebellion had settled down, he was accepted into the NWMP as an Inspector. It was October 20, 1886.

Over the years, Constantine had fostered a unique and colourful personality. He was reputed to be a man of few words, blunt as a bear and as exacting as a jigsaw. Within NWMP circles, he was known to be dependable and fair minded. He mixed common sense with justice to settle disputes, and he was a proven and seasoned traveller. And, at the moment of the Gold Rush, he was available. When Ottawa bureaucrats were considering whom to send to the Yukon, their first choice fell also to Constantine.

Around 1894, there arose in Ottawa a significant concern about the influx of prospectors into the Yukon but more especially about the lack of any official representatives of government in the region. Klondike gold translated into prosperity otherwise disguised as an opportunity to collect taxes. A proposal was made to the NWMP that Superintendent Constantine be detailed to rectify the situation.

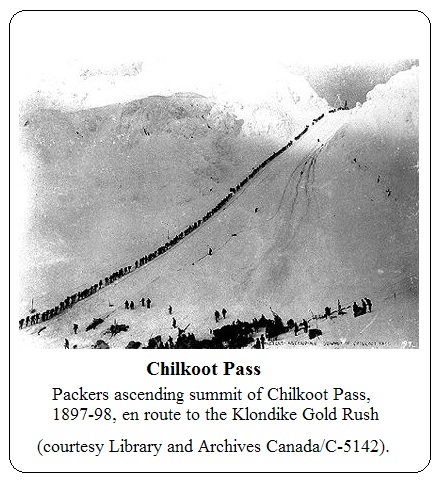

On his advent trip to the Yukon in 1894, Constantine chose Reg.#1694, Staff Sergeant Charles Brown as his travel companion. The jaunt was intended to be an assessment of required needs for a follow-up contingent of NWMP. In June, they boarded the train in Regina, and upon their arrival in Victoria, they boarded the steamer Chilkoot and sailed for Alaska. This would become the same route which the NWMP and all the gold prospectors would follow in subsequent years. The team stopped briefly at Juneau, Alaska, then they continued onward to Skagway and Dyea. It was Constantine and Brown's intentions to cross the coastal mountains via the Chilkoot Pass and to the lakes and hire a boat and float down to Fortymile --a total distance of 600 miles from Dyea.

But there were unforeseen gitches. Much like the experience of previous explorers, Constantine learned early on that the Pass was jealously protected by the Chilkoot Indians. Not only did they terrorize newcomers, but they were known as unscrupulous and shrewd. They earned only contempt from Constantine who had little time and patience to haggle with them. In his book, Maintain The Right, author Ronald Atkin said that Constantine could not fail but to mention the Chilkoots. In his diary, Constantine wrote that the Chilkoots, "seem to take in but one idea, and that is how much they can get out of you." (Atkin: 302). The whole thing was frustrating to Constantine, and his exasperation with the Chilkoots had become wholly apparent.

From the outset, hardship and frustration were companions with Constantine and Brown, not tomention unexpected costs. They had to pay carrying fees of fifteen cents per pound for their 800 pound baggage over the fourteen miles from Dyea over the Chilkoot. An additional twenty five cents was charged each time they had to be carried across frequent icy streams. Eventually, they made it safely through the Pass, but the crossing was taxing on Constantine.

The Pass was more arduous than previously thought, and he wrote in his diary that the trip was, "a hard and dangerous climb over the bare rocks and soft snow most of the distance, sinking nearly to our knees at every step." (Atkin: 302). On the other side, their arrival at Lake Lindemann was supposed to be a relief.

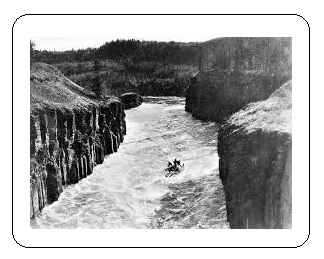

Boats were not available for purchase at Lake Lindemann so they strung together a crude raft and floated it down to Lake Bennett. Here, good lumber was available for making crafts which would float, but the boat building idea was so tiring that Constantine tagged the place 'Lake Misery'. They were part-way through the completion of their boat, when they met two miners who agreed to help the team to Fortymile. But for $125.00. And, far more unexpected danger lay ahead on the river before they were to reach their destination of Fortymile.

Constantine and Brown were far from being accustomed to river travel. Angry currents, cold water and high falls in the range of fifty feet met the team. Whirlpools raced through deceptive calm water and every effort was necessary to push their craft away from razor edged rocks lining the river. Although the two miners help was beneficial and fully necessary, all the team's supplies had to be portaged around the river's canyon. In the meantime, the torrential rain never stopped.

They reached Fortymile on August 7th 1894 and a relieved Constantine wrote, "Am glad trip so far is done. Was well tired and sick of the everlasting river. Had just enough grub to see us through." (Atkin: 303). At the time, neither Constantine nor Brown realized how taxing the cold, damp and treacherous trip had been on their own health.

Nevertheless, Constantine's mind was spinning in forward motion. He knew that he had to soon return to Regina, and begin plans for a second trip to the Yukon with a larger contingent of NWMP.

At this moment, however, with the arrival of Constantine and Brown, the miners in the vicinity soon came to realize that their carefree, absence of law days were now over. Constantine declared himself to be chief Agent of the Dominion of Canada which gave him wide ranging powers over ever matter of any worth in the Yukon. He knew too, that taxes would not be popular, but his firmness, quiet resolve and reasoning made the medicine easier to accept among the miners.

At the same time, Constantine and Brown helped affirm Canadian sovereignty over the Yukon, and they collected a modest sum of customs duties from the miners on the Canadian side of the Alaskan border. Prior to leaving for Regina, Constantine purchased 320 acres of land for the future construction of a police detachment in a strategic location across the Fortymile River. Then, on September 3, 1894 he sailed downriver by steamer and he completed the return trip to Victoria by a US revenue cutter and the British Warship H. M. S. Pheasant. (Summarized from Atkin: 304)

Constantine submitted his needs assessment report to Ottawa bureaucrats upon his arrival back in Regina. He recommended that a strategic police post be built at Fortymile, and he asked for a NWMP contingent of forty men to include a medic and two Officers. He was very particular about the quality of men whom he wanted for his Contingent. Constantine wrote, "They should be of large and powerful build -- men who do not drink." (Atkin: 304). Politicians may have been appreciative of his report but they cut his request of forty men in half. Only 20 men for his Contingent were approved.

On June 1, 1895, Constantine led the first permanent contingent of NWMP to the Yukon. The group included Medical Surgeon O.102 Alfred Ernest Wills, Inspector D'Arcy Strickland and seventeen constables and NCO's. The Contingent left Regina, SK for Seattle, WA then they boarded the steamer Excelsior to Juneau, Alaska. Of interest was that the police contingent also included Mrs Constantine and their son Francis as well as Mrs Strickland and their baby. Sailing north was unusually smooth, but Sergeant Murray Hayne noted how the whole Contingent, including their food supplies, and their baggage would have been washed overboard if the Excelsior had hit rough seas.

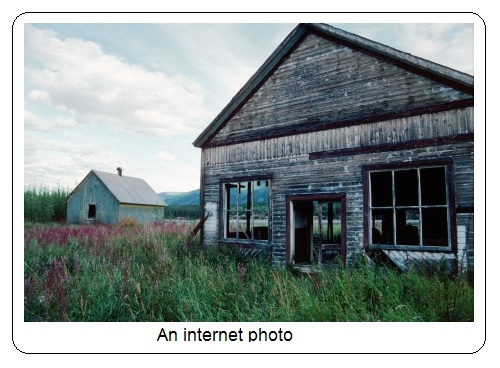

After a nineteen-day haul, and 2000 miles up the Yukon River, the Contingent arrived at Fortymile on June 26th, 1895. The Contingent immediately began to establish themselves; clearing woods, searching for good lumber and building new quarters. The settling down process was plagued by poor out of doors conditions -- the chosen location to build a fort was a swamp, and rain and mosquitoes made all their efforts simply miserable. They were forced to sleep in wet clothes.

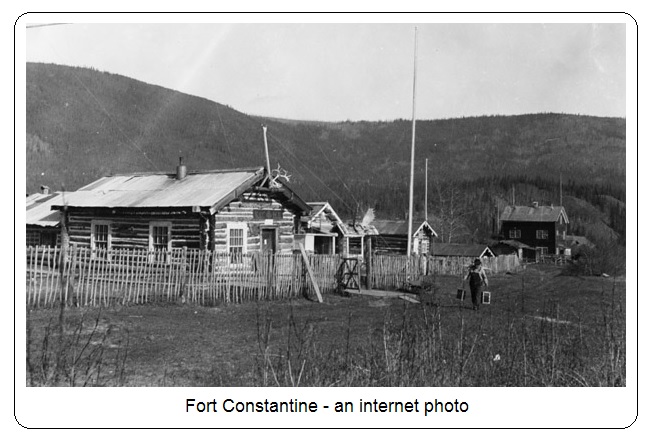

Yet, in spite of the alternating heat, rain and flies, the Contingent successfully built nine buildings by November. It may have been home, and they named the place Fort Constantine. The Contingent proved that they would be well established in the region before the mass of miners flooded into the Yukon.

Constantine was now recognized as Commander of the NWMP and Chief Magistrate, as well as Home and Foreign Secretary. According to his own recollection, he used three tables to keep organized and to separate the work requirements of each role.

From early on, Constantine realized that the duties assigned to the NWMP would be very broad and mostly unscripted. As well as the general maintenance of law and order, the Mounties were ordered to set up customs posts at the summit of the Chilkoot and the White Pass. The Mounties also mandated that all gold seekers had to have a ton of goods necessary for a year's survival in the formidable Canadian North. Much of this favourable, life saving activity was due solely to Charles Constantine.

Under Constantine's leadership as well, the presence of the Mounties put an end to spontaneous miners' meetings, talk of lynchings and vigilante justice. The Mounties collected liquor taxes, and customs duties, but there was no nonsense, and prospectors took the word of the Mounties seriously -- the style of the Mounties law enforcement stood in stark contrast to the rag tag marshalls on the American frontier where guns were called in to settle disputes. The Mounties set conciliatory tone in the Yukon quite different from their American neighbours. Quietly and determinedly, the NWMP imposed new standards on the Canadian side of the border. This too was a reflection of Charles Constantine's quiet determination, persistence and solid leadership. In the meantime, he was promoted to Superintendent -- a cherished recognition which had not come easily.

After a tough four year stint, an exhausted Constantine left the Yukon in June, 1898. He had been held in high regard by both his men and the miners and he left behind a wide host of good friends and well wishers. He felt sentimental yet appreciative about his departure from Fort Constantine, so he wrote, "Thank God for the release." (Atkin: 347). Not only had the Yukon tour been exhausting and harsh, but its toll would be felt on Constantine's body in the years ahead.

Superintendent Constantine left a legacy worthy of a great Canadian. His life's work may not be as well known as some other Canadians, but his name lives on in Canadian history especially in the Yukon. At the core of his personality was a strong, determined and honest person. It is unbelievable what he accomplished in terms of workload. The RCMP is all the more rich for having had Superintendent Constantine among their ranks. It is important that he is not edged out of RCMP history and be forgotten.

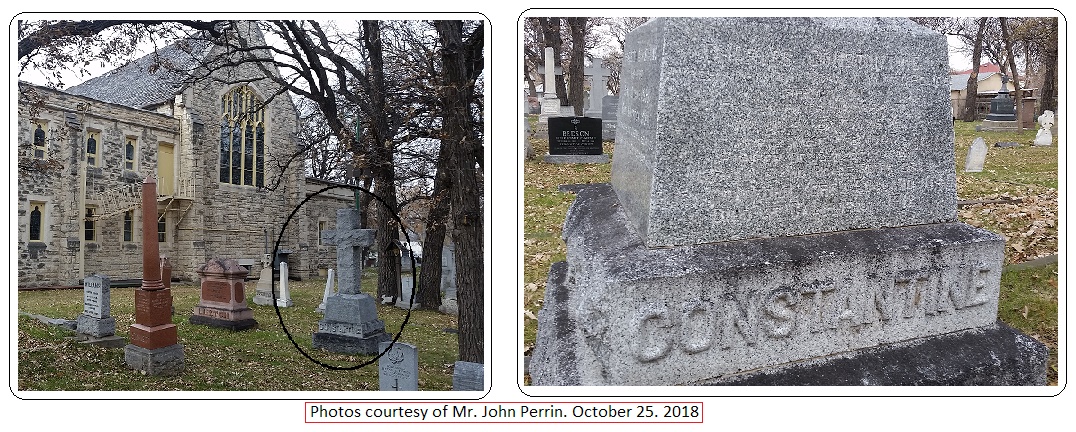

By 1911, after long years of rigor and harsh living conditions, Superintendent Constantine was in failing health. In 1912, he was granted Medical Leave and he traveled to southern California for sun and rest. He died at Long Beach, California on May 5, 1912 while on Medical Leave. He was 62 years of age. Superintendent Constantine was buried in St John's Anglican Church Cemetery in Winnipeg, MB near the grave of his friend O.40, Superintendent Sam Steele.

One report said that Superintendent Constantine died in Long Beach, California, USA, but Canadian author Pierre Berton wrote in his book: Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush (p.405), that he died in 1912 in San Francisco, USA.

Fort Constantine, Yukon Lat: 64·26·00N Long: 140·32·00W) was named after its founding Officer 0.79 NWMP Superintendent Charles Constantine.

Reporting from Fort Healy,

J. J. Healy

August 23, 2016

Atkin, Ronald. (1973). Maintain The Right. MacMillan London, Ltd.

Berton, Pierre. (1972). Klondike: The Great Gold Rush. 1986-1899. McClelland and Stewart Limited. Toronto, ON.

Source. Johnny Healy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Healy_(entrepreneur)

Source:http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/expositions-exhibitions/gendarmes-mounties/en/ sovereignty/goldrush/klondike/