True and Fascinating Canadian History

A Mystery of the Mounties:

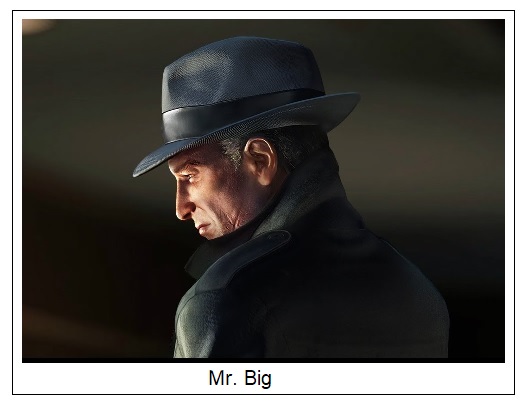

Mr. Big Once Bruised & Bounced

by J. J. Healy

When it's all boiled down, drained and distilled the principle mandate of the criminal investigator is to collect sufficient material evidence to prosecute the accused. But, the crown jewel of the entire investigation is a confession -- a prized confession then becomes a key piece of evidence for the prosecution and an almost sure route to a conviction. At least that’s the theory which drives criminal law instruction at the RCMP Academy. As fresh cadets embark on new careers in policing, the sole commandment which they are expected to remember, apart from their badge number is, “Aim your sights on a confession.”

Today, however, far too many cases exist where police officers use questionable tactics to obtain a confession -- alarm bells screech followed by concern and severe criticism by the courts. Importantly, the lesson which should be stressed over and over again is that any confession given to the police must always be offered voluntarily by the accused and if not, the confession will not be included as evidence. A confession offered voluntarily is a shining star whereas a confession not offered voluntarily is equivalent to dust on the courtroom floor.

During the voir dire, any questionable interrogation techniques by the police come under scrutiny. Voluntariness of the confession is weighed against such factors as; any threats or promises, perceptions of oppression, the clear, lucid mind of the suspect, and any police trickery. In “The Mystery of the Mounties: Mr. Big Once Bruised & Bounced” the RCMP had conducted a very intense criminal undercover sting operation, but in court the whole issue of voluntariness came under microscopic scrutiny.

More defects were found with the Mr. Big sting than had ever been expected or anticipated. The RCMP was severely reprimanded for its distasteful conduct, and the harm done to the RCMP's main suspect was incalculable. The Supreme Court shot from the hip and did not mince words in its blunt assessment of this particular operation. Undoubtedly, the case holds extremely valuable lessons for all police officers especially if they intend to employ Mr. Big again in future criminal investigations.

Few cases in recent Canadian jurisprudence has received as much publicity as R. v. Hart. Nelson Hart, a father of three-year-old twin daughters was convicted in 2007 of their murder back in 2002. At first, the case appeared open and shut. The jury did not believe Hart's reasoning, and he was convicted. But, Hart appealed his murder conviction, and in 2014 Canada’s Supreme Court surprisingly found the confession which Hart made to RCMP undercover operators had fallen far short. The confessions were ruled inadmissible. The reasons given by the Supreme Court to dismiss Hart’s confession were lengthy, thoughtful, detailed and instructive. Hart was set free.

There was no doubt that Hart had confessed to murder, not once but a couple of times. So, how was his confession defective? How could Hart have confessed and yet be found not guilty? How could the RCMP’s case have ever gone off the rails? These are all mysterious questions for one to consider. To fully understand the case, one must go back to the beginning. A summary of the case from the Supreme Court judgement follows here.

Hart’s twin daughters drowned on August 4, 2002. Almost from the start, the RCMP suspected that Hart was responsible for their deaths. But, the RCMP lacked direct evidence to charge him with murder. Hart was released and he went home. Time passed. Two years later, undercover RCMP members launched a “Mr. Big” sting operation.

In 2005, Hart was charged with murder, and his trial began in 2007. It is important to note that at the time of the sting, Hart was a complete loner. He was unemployed and socially isolated. He rarely left home and if he did, he was accompanied by his wife. He lacked life experiences, and he lived in extreme poverty. He might have also been suffering from deep depression. Hart was sick, vulnerable, uneducated, naive and a person with no hope or future means of support. This assessment of a desperate Nelson Hart would eventually come into play especially when the court assessed Mr. Big.

One day, Hart innocently met one of the undercover RCMP on the street, and from that point on, he was strategically and methodically pulled into Mr. Big’s fictitious criminal organization. Hart worked with the undercover officers, was befriended by them and was paid by them.

Over the next four months, Hart participated in 63 sting “scenarios” all arranged by the undercover RCMP officers. He was paid more than $15,000 for the work. He was also sent on several trips to cities across Canada, he stayed in hotels, and occasionally dined in expensive restaurants during the trips, all at the fictitious organization’s expense. Over time, undercover officers became Hart’s best friends and Hart came to view his new friends as true brothers. At one point, according to one of the undercover RCMP members, Hart made an out and out statement in which he confessed to having drowned his two daughters. But, that was just for starters.

Eventually, Hart was told that he would meet the organization’s head -- a meeting was arranged akin to a job interview between Hart and “Mr. Big”, the man purportedly the boss of the fictitious criminal organization. At that point, “Mr. Big” interrogated Hart about the death of his daughters, seeking a confession and at first Hart denied any responsibility, but then he confessed to drowning his two daughters. Two days later, Hart went to the scene of the drowning with an undercover RCMP and Hart explained how he had pushed his daughters into the water. He was then arrested.

In this instance, and others as well, the Hart case proved how police officers sometimes have accumulated circumstantial evidence of a crime, which in and by itself can show the accused in a poor light, but more direct evidence such as a solid confession is necessary to: a) place the accused squarely and surely at the scene, b) to provide exacting details of the crime which the public would not necessarily know, and c) to link the accused directly to the victim. Once more, the value of a full confession within the context of a serious police investigation cannot be underestimated. But, one must always ask, “How was the confession obtained, and was it offered voluntarily?” "Will the manner in which the confession was obtained leave a sour taste in the mouths of Canadians as well the court?" The answers to these questions, caused the court to only find huge faults with Mr. Big.

At the Supreme Court level, the whole “Mr. Big” sting came under severe scrutiny and study. The court noted that Mr. Big tactics, "come at a price." In the Hart case, Mr. Big demonstrated far more flaws and shortcomings than the RCMP expected. It might be helpful if the flaws of Mr. Big were clearly spelled out. The list was taken from the Supreme Court judgement. (R. v. Hart).

First, the Court said that, “Confessions to Mr. Big during pointed interrogations in the face of powerful inducements and sometimes veiled threats — raised the spectre of unreliable confessions.”

Second, “Unreliable confessions provided compelling evidence of guilt and presented a clear and straightforward path to conviction. In other contexts, they have been responsible for wrongful convictions — a fact we [the Court] cannot ignore.”

Third, “Mr. Big confessions are also invariably accompanied by evidence that shows the accused willingly participated in “simulated crime” and was eager to join a criminal organization. This evidence sullied the accused’s character and, in doing so, carried with it the risk of prejudice.”

Fourth, “Experience in Canada and elsewhere teaches that wrongful convictions are often traceable to evidence that is either unreliable or prejudicial. When the two combine, they make for a potent mix — and the risk of a wrongful conviction increases accordingly. Wrongful convictions are a blight on our [Canadian] justice system. We must take reasonable steps to prevent them before they occur.”

Fifth, “Mr. Big operations also run the risk of becoming abusive. Undercover officers provide their targets with inducements, including cash rewards, to encourage them to confess. They also cultivate an aura of violence by showing that those who betray the criminal organization are met with violence. There is a risk these operations may become coercive. Thought must be given to the kinds of police tactics we, as a society, are prepared to condone in pursuit of the truth.”

The Supreme Court judgement in R. v. Hart, 2014 is very, very lengthy. However, the entire critique of Mr. Big can be summarized in a couple points:

First, statements by the accused engage the cornerstone principle against a person's self-incrimination, and Canadian courts have tended to exclude statements obtained in breach of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms on the ground that admission on balance would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. Statements obtained in violation of the principle against self-incrimination will almost always be excluded.

Secondly, if the statement is reliable but was rendered unconstitutional because of concerns about coercion or state conduct, its admission would also bring the administration of justice into disrepute. This case is no exception; both the risk of a miscarriage of justice and the abusive police conduct call for exclusion.

In this case, all factors considered clearly point to Charter violations. The Court said, "The police procured a confession by preying on the respondent’s particular vulnerabilities in a complex sting ... the confession is of dubious reliability and is unsupported by any corroborative evidence or detail." Accordingly Hart's confession was excluded as evidence. Some of the Court's unpleasant findings as outlined in their judgement are repeated here almost word for word:

First, "the RCMP employed extensive state resources to prey on Hart's lack of education, intellect, and life experience, his social isolation, and his extreme poverty. Mr. Hart’s beloved friends gradually involved him in an increasingly serious world of criminality, beginning with dealing in supposedly stolen goods and eventually portraying the organization as a violent international group with a boss who made the Hell’s Angels look like “flunkies”. As Hart involved himself in more dangerous and illegal activity, his pay increased."

Secondly, "the degree of harm caused by the Mr. Big operation is also relevant. The respondent was so thoroughly enmeshed in his make-believe world that upon his arrest, his first reaction was to call his supposed “friend”, Jim. It should have come as no surprise, particularly to the officers who knew him so well, that Hart was devastated to learn that his new life, where he had felt valued and respected, had all been a carefully constructed illusion. He had no friends. He had not been employed because he was “smart”: rather, he was thoroughly duped."

"The respondent developed paranoia, believing that everyone was part of the “sting” against him, and was unable to trust his lawyers and even his own wife. He was eventually committed to a psychiatric hospital, and amicus curiae made submissions on his behalf at the appeal. Such an emotional collapse is by no means a prerequisite to a finding of abusive state conduct. However, this kind of psychological manipulation by state agents harms not only the suspect but the integrity of the justice system."

The Court said, "This case is more akin to entrapment. The police employed the power of the state to create an elaborate invented reality, designed to exploit a vulnerable person, introduce him to criminality, and force him to incriminate himself.

The Court also said, "I am greatly troubled by the extreme lengths to which the police went to pursue the respondent, exploiting his weaknesses in this protracted and deeply manipulative operation. The abuse of process doctrine always remains independently available to provide a remedy where the conduct of the state rises to such a level that it risks undermining the integrity of the judicial process."

"In my view, as will be clear from my discussion of the state conduct in this case, that threshold is met. To condone the actions of the police would “leave the impression that the justice system condones conduct that offends society’s sense of fair play and decency” However, given the outcome of this appeal, it is not necessary to discuss this issue further."

The assessment of this case by the Court was not favourable to the RCMP. Mr. Hart suffered seizures both before the investigation began and during the operation itself. Yet, undercover operatives continued to allow him to carry out specific assignments all the while under RCMP eyes.

The Court did not say that Mr. Big operations should be totally discontinued or even that Mr. Big should be placed on the disabled list. But, according to the Court, this particular case was disgusting. In the Hart case, Mr. Big was definitely left bruised, broken and in desperate need of repair. That at least, is one lesson that all police officers can learn about Mr. Big from Canada's Supreme Court.

It is a total mystery why leadership within the RCMP chain of command did not measure the lack of mental competencies offered by Mr. Hart and cancel this thing before it was ever launched. Surely the RCMP has an extensive check-off list which would calculate the ups and downs of each operation and its planned target.

The RCMP is known to do alot better.

The end.

Reporting from the Fort,

J. J. Healy,

April 20, 2018

R. v. Hart, 2014 SCC 52, [2014] 2 S.C.R. 544