True and Fascinating Canadian History

Web2016.jpg)

A Mystery of a Mountie:

And A Commissioner's Fall

by J. J. Healy

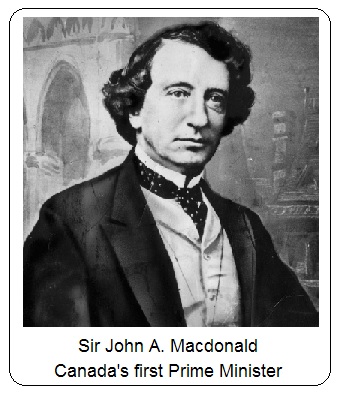

Some Canadians could be led to believe, quite naturally, that solid leadership skills are the only factor in the selection of the RCMP Commissioner. At least, that’s the pitch that’s put on sale out front. But, from the dawn of the NWMP, it has been evident that success for the top post in the RCMP depends as much on politics as it does on leadership qualities, and the true method of choosing the Commissioner remains much the same today as it did in 1873. The appointment of the RCMP Commissioner is the sole and exclusive prerogative of the Prime Minister.

If in fact, however, there is a saw-off between leadership skills and politics for choosing the Commissioner, an aspiring Officer might well pause and ask him or herself, “Is it worthwhile to spend time developing the essential and traditional skills of a police officer including; on the street experience, a wide range of jobs and variety, trans Canada transfers, language skills, and an investment in higher education, or is nurturing politics the more direct, efficient, rewarding and the most certain route to the top”?

Web2016.jpg)

In the early years of the NWMP, say between 1886 and 1900, one man in particular dominated the full skyline of the Force; Lawrence William Herchmer. In 1886, Herchmer was unexpectedly chosen by the Prime Minister as the fourth Commissioner of the NWMP, while other long serving men such as Assistant Commissioner L. N. F. Crozier, and Superintendent Samuel Benfield Steele were overlooked. At the time, Herchmer was a virtual unknown to the NWMP, whereas several other NWMP had faithfully served Canada, and the Force and had paid their dues.

Crozier, for instance, was the senior Assistant Commissioner, he was reputed to be a hard worker and an efficient Officer, he had wide experience with the Sioux under Sitting Bull, and he had also been highly successful in all his policing assignments including conflicts related to the Northwest Rebellion.

Yet, upon hearing of Herchmer’s appointment to Commissioner, Crozier resigned, and his departure created deep disappointment within the NWMP. In his book titled: The Law Marches West, retired NWMP Officer Sir Cecil E. Denny wrote about the chill which resulted after Crozier’s resignation, Denny said, “...his work during the Rebellion and in fact his success in all he undertook stamped him as one of the most capable men of the Force. The commissionership was certainly due him, not only for the services he had rendered but because he was next in seniority. His resignation on the position being given to an outsider was regretted by all his companions in the force.” (Denny: 226). In addition to Crozier, there were many other Officers who wanted to resign, but who decided to remain with the NWMP as they were men with families and they had no other reasonable options.

Web2016.jpg)

Superintendent Sam Steele too was overlooked. Steele had years of police experience and he had brought fame to the Force; he had served in a number of critical Western Canada posts, he had settled disputes of all kinds, he personally knew each of the original Officers in the NWMP, he had risen through the ranks from Constable to Superintendent, and he had devoted his entire life to the Force. For years, more than just a few people held high expectations that Sam Steele would someday be the Commissioner of the famous Force. But, that was not to happen.

In the short story which follows, parts of Herchmer’s career will be reviewed. And, while Herchmer had strengths, and he enjoyed a certain degree of success, he also instigated conflict with personal relationships, and his career in the NWMP was encircled with controversy. Without any doubt, Herchmer made major mistakes along the way, and the sum total of his errors cost the man a high price. Eventually, he left the Force sad, disenchanted and lonely -- and, the reasons for his demise will become evident in “The Mystery of the Mountie: And a Commissioner’s Fall”. Perhaps, the whole thing was not fair, but there is a lesson or two here also for all police officers -- or, at least those with sky high aspirations.

The appointment of Lawrence William Herchmer to the Commissioner’s job in 1886 sent a deep freeze most especially through the upper ranks of the NWMP. After Commissioner Irvine’s departure, it was naturally expected, at least inside the NWMP, that one of the other senior Officers next in line would be chosen. And yet, resignations from within the NWMP such as Crozier’s, did not seem to faze the Prime Minister. In recent years, word had reached Ottawa that the NWMP under Commissioner Irvine’s tenure had become somewhat broken, dysfunctional and disruptive, and the Prime Minister may well have thought that he had no guarantee that things would change for the better if the new Commissioner was appointed from within the current crop of Officers.

Web2016.jpg)

In the history books, the years under Commissioner Herchmer are described as no less than tumultuous for the NWMP. There was no doubt that Herchmer was dedicated, however, his personality and irrational thinking often caused him to be off sides with too many people -- senior Officers and bureaucrats alike. But first, one has to look at his background.

Herchmer had a curious if not an unusual head start to his career. He was born in Oxfordshire, England, and it was in England that he also received his early education. After schooling, he served for three years in Ireland and India with the British Army, and then he immigrated to Canada where he headed for Kingston, Ontario. He was but twenty-two years of age.

Herchmer was fortunate indeed as he had inherited property in Kingston from his family, and by coincidence, his property was in close proximity to property once owned by Sir John A. MacDonald. It was not so long before that the MacDonald family and the senior Herchmers were friends and practically neighbours. At the time, Lawrence Herchmer may not have fully appreciated how the cozy connection between the two families would bode well for his career sometime well into the future.

Although Herchmer may have originally planned to settle down in Kingston, he left after a spell and travelled to Canada’s North West. He was first employed as a Commissariat Officer in the Boundary Commission which was responsible for laying down the dividing line of the US-Canada border. Herchmer’s work and extensive travel with the Boundary Commission was considered beneficial as it gave him valuable experience in Canada’s pioneer country which he otherwise would not have received had he remained within the confines of urban Kingston.

Web2016.jpg)

After the Boundary Commission, Herchmer tried his hand at business. He moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, and he founded the Redwood Brewery which he ran for ten years. He then became an Indian Agent for the Province of Manitoba. By this time, Herchmer was forty six years of age and, looking back, he could lay acclaim to a somewhat varied career mix of military, business and government affairs -- and, most importantly his family name which, it turned out, was his most valuable asset.

Lawrence Herchmer was not the Prime Minister’s first choice for Commissioner of the NWMP. MacDonald’s eye first fell on Lord Melgund who had arrived in Canada in 1883, and who had acted as a Military Officer to the newly appointed Governor-General Lord Lansdowne. If the Prime Minister was looking for someone with a military pedigree then Melgund would have been his man -- prior to his employment with Lord Lansdowne, Melgund had also been Chief of Staff to General Middleton during the Northwest Rebellion.

But, Melgund declined MacDonald’s offer for the Commissioner’s job on the grounds that travel would keep him away too long from his wife. Only then did Lawrence Herchmer become the Prime Minister’s next choice -- and the selection of Herchmer as the new Commissioner of the NWMP was said by astute observers to be no less than astonishing.

Herchmer may have been as surprised as anyone by his new appointment, but it seems that he quickly recovered, and he immediately set out, somewhat determined, to correct whatever ills had befallen the Force under the Irvine regime. Herchmer was reputed to be a disciplinarian, and an able administrator with a fixation on fine details. He was also strong willed. In Herchmer’s mind there was work to be done, with changes to be made, and he directed that they be put into effect straight away including the following; applications for employment in the NWMP would be closely scrutinized, disciplined would be tightened up and enforced, medical exams would become mandatory, living conditions would be improved, experienced police officers would be encouraged to remain and to make the NWMP a career, and pension benefits would be explored with the Canadian government.

Web2016.jpg)

Without question, Herchmer had set lofty goals for himself as well as for the NWMP, and only time would tell if his priorities would be achieved. But, in order for Herchmer to do anything, he also needed to smooth the path and nurture the support of his fellow Officers -- all of whom had been overlooked for promotion. From their viewpoint, Herchmer did not belong. He could well expect some resistance from inside the NWMP.

Progress was uphill for Herchmer almost from the outset. His intentions for progress may well have been laudable, but his personality was short and curt and it grated on the other Officers who were expected to carry out his orders. In his famous book entitled, “Maintain The Right: The Early History of the North West Mounted Police, author Ronald Atkin described Herchmer as, “Stubborn, opinionated, and dedicated (in his fourteen years as Commissioner he took only two weeks’ leave), Herchmer was fiercely determined to eradicate the laxness of the Irvine regime and to instill pride in the force he had so surprisingly been chosen to command”. (Atkin: 258). It was well noticed that he essentially never took annual holidays and this unusual behaviour might well have reflected on Herchmer’s dedication, or his personal insecurity or his lack of faith in his fellow Officers. And yet, in order to achieve all the changes which he so desperately wanted to make, Herchmer needed their full support, but it was not offered or forthcoming due in part to his gruff manners, his estrangement from other Officers, and a list of ill conceived decisions.

Web2016.jpg)

For sure, Herchmer must have known that he ought to be cautious about making any changes to the status quo straight away, and that he would be fighting strong head winds emanating from inside the NWMP, but especially from his senior Officers all of whom felt strongly they were far more deserving than he for the Commissioner’s post.

To the surprise of everyone, one of his first announcements was to promote his brother from Superintendent to Assistant Commissioner and to replace the departing Crozier. The decision was not in the least warmly received. On the one hand, the promotion of his brother, William Herchmer, as Second In Command gave the Commissioner some confidence that he had a trusted ally nearby, but on the other hand, his decision further aggravated and annoyed an already disgruntled group of Officers who saw their careers stalled and put on hold.

In the meantime, trouble was brewing further west. The NWMP in the Edmonton area had staged a brief yet serious mutiny, and it had a direct and not so positive effect on the Commissioner. Briefly, it seemed that a group of constables were more than irritated and also put in a rebellious mood about their overall living conditions; poor sanitation, poor rations, and an over abundance of bed bugs and fleas in their sleeping quarters. The group disobeyed the lawful orders of their supervisors. Eventually, the malcontents were arrested; nineteen were charged and sent to Regina for trial, six went to prison for a year, and the remainder were fired.

But, rather than learn from the experience and use the after-effects of the mutiny to inspire his men, Herchmer yet again antagonised his subordinate Officers by doubling down on discipline, and then starting a campaign of needless memos which he sent to all four corners of the North West. His managerial habits were viewed as irritating and he continued to chafe the under skin of his senior Officers. The gulf between he and the other Officers was already somewhat wide, but it continued to expand over the ensuing years.

Web2016.jpg)

One senior Officer, in particular, continued a running battle with Herchmer. Superintendent Richard Burton Deane was selected as the Commissioner’s Aide, but he refused to back down whenever something was set amiss by the Commissioner. The intimate setting provided Deane with a first hand and ripe opportunity to watch the Commissioner’s managerial manners and methods which Deane would describe as picky, petty, and padded with jealousy -- and Deane was able to accumulate lots of examples. In one instance, the Commissioner chose Fort MacLeod to act out a personal vendetta.

At the time, Superintendent John Cotton was the Officer in Charge at Fort MacLeod, and he was ably assisted by a personal friend Veterinarian Surgeon Dr. George Kennedy. The reasons are not clear, but the Cotton-Kennedy alliance annoyed the Commissioner, and his displeasure was quite obvious to Superintendent Deane, who wrote, “This was the combination that Herchmer used to call “the MacLeod clique,” and between him and it there was bitter enmity. It goes without saying, therefore, that when the Herchmer family came into power the first sign of attack on “the MacLeod clique” showed itself in orders transferring ‘C’ Division and its Officers to Battleford, a post in the far north about five hundred miles from MacLeod….Dr. Kennedy said he would not go and [he] resigned his commission...” (Deane: 34). In hindsight, it may have been more advantageous had Herchmer left the Cotton-Kennedy friendship rest, and instead turn his energy towards other more critical issues. Precious time, energy, and spirit was lost on internal squabbles needlessly raised by the Commissioner.

Web2016.jpg)

About the same time, Herchmer insisted that the flag at ‘Depot’ Headquarters not be flown when he was not on site. The rule, according to Deane was most unusual and very unexpected. Superintendent Deane put it down to another irrational decision of the Commissioner, and he said, “This was just the kind of thing that Mr. Lawrence Herchmer did, and there was a hoot of derision from all over the country at the new rule, which could not be kept secret. I have said enough to show that he was quite an impossible man to work with. His appointments did not bespeak the welfare of the public service as the first consideration. (Deane: 36). Over time, it was apparent that Deane put little or no stock in most decisions made by the Commissioner, and it became increasingly apparent that he (Deane) was considered by the Commissioner as part enemy.

Deane and the Commissioner continued to share frequent and explosive arguments which sometimes bordered on hysteria. It just so happened that a major argument between the two of them hit a high pitch on the same day that Mr. Frederick White, the Comptroller of the Force was visiting ‘Depot’ from Ottawa. An exasperated Deane said, “I had dry nursed [Herchmer] for a full year and was heartily sick of the job.” (Atkin: 259). As a result of the latest feud, Frederick White transferred Deane to Lethbridge, AB., but the animosity between he and the Commissioner continued, and the significant distance between NWMP Headquarters in Regina, SK. and Lethbridge, AB. made little or no difference.

Web2016.jpg)

Superintendent Deane was not the only Officer to suffer the wrath of the Commissioner. After hearing about a case of drunkenness at Maple Creek, SK., the Commissioner wrote to the Officer Commanding, Superintendent Antrobus. The Commissioner said, “Your division affords me more anxiety than any other, and there are more serious breaches of discipline than in all the other divisions together. I cannot but ascribe this to your weakness and want of tact…” (Atkin: 260). Eventually Antrobus was suspended from duty, and the Commissioner undertook to shoulder the sentiment that he was fully surrounded by a band of enemies. In a letter intended for Comptroller Frederick White, the Commissioner wrote, “My life is hardly safe while certain Officers remain under my command.” (Atkin:270).

Although the Commissioner was tough on Antrobus, he was far more severe on Inspector Mills who, on one occasion, was also reported to be drunk. The Commissioner offered Mills an option; resign or be dismissed. The Inspector resigned. Inspector William Brooks met the same unpleasant ending. He too was accused by the Commissioner of being intoxicated during a murder investigation. Brooks was suspended from active duty then he resigned.

In a subsequent case, another Officer under the command of Superintendent McIllree was also reported to be intoxicated. It too caught the attention of the Commissioner who wrote, “If he agrees, purchase a ticket for him and see that he leaves.” (Atkin: 261). There is no doubt that Herchmer was particularly strict whenever his subordinates abused liquor which was nearly always present in those days and very abundant.

As a result of an increased number of complaints about drinking, the Commissioner retaliated by increasing discipline which only had the effect of increased dissatisfaction among all the ranks and more desertions. But, whether or not Herchmer was to blame for all the faults of the organization, or if his managerial style simply provoked the Officers and the men of the NWMP to drink more and act out while intoxicated is only speculation.

Web2016.jpg)

In the meantime, another squabble broke out at ‘Depot’ between Inspector A. R. Cuthbert’s wife and Mrs Herchmer over the sharing and use of a constable who was employed as a servant and stove-stroker. The Commissioner reported to Ottawa that Inspector Cuthbert was insubordinate, but the pesky reports caused Comptroller Frederick White to become more and more incensed with Herchmer’s petty behaviour.

About the same time, the Commissioner ordered Inspector James Wilson to be transferred from Pincher Creek to Regina but Wilson resisted the move on the grounds that his wife was pregnant at the time. Mrs Wilson’s pregnancy caused Herchmer to become riled, so the Commissioner decided to publish a memo which said, “In future, I’ll have to order married officers to send in monthly reports as to their wives’ condition before I can order them to move.” (Atkin: 271). The memo highlighted Herchmer’s intolerance for common sense.

But, the Commissioner was equally insensitive with the lower ranks. Author Ronald Atkin described the action which Herchmer took in a case of desertion. Atkin reported, “He [Herchmer] ordered Constable E. Dubois be shackled with a ball and chain during his twelve months’ imprisonment for deserting at Battleford”; but there was more, “in front of a parade he threatened to report Inspector Frank Norman to the Prime Minister if his division did not drill better; and he promised to post some officers from Regina for refusing to organize a dance when he requested them to do so.” (Atkin: 271).

Web2016.jpg)

There can be little doubt that Herchmer might have accomplished far more had he chosen to mend fences along the way, but his clashes were not limited solely within the NWMP -- he had running battles with Mr. Nicholas Flood Davin, editor of the Regina Leader, as well as with Mr. Charles Wood, a former NWMP who edited the Fort MacLeod Gazette. After each argument, both of these men had a golden opportunity in the press to show the Commissioner in a distasteful and bad light.

The continual round of fights did not enhance Herchmer’s overall reputation within the NWMP, nor did the conflicts have a positive effect on his popularity within the larger community.

The upshot of all this fuss was that an inquiry was ordered in early 1892 to look into Herchmer’s harsh management style within the Force, and his tyrannical conduct. Eventually the inquiry cleared Herchmer of any serious wrongdoings, and there was absolutely nothing to link Herchmer with any form of dishonesty or any improper business dealings.

Instead, Herchmer was found guilty of “too much zeal, and misapprehension of his powers.” The judge did, however, conclude his report by saying, “A very large proportion [of the charges] are attributed to infirmity of temper, brusqueness of manner or hasty conduct...I found the relations existing between the Commissioner and a large number of officers of the Force very much stained. I am not, however, prepared to state on whose shoulders the blame lies for this state of things.” (Atkin: 271). The judge’s report was sent to Ottawa, and at the same time Comptroller Frederick White showed signs that he was growing tired of Herchmer. The Commissioner had few supporters in Ottawa or Regina. Surprisingly, but after the inquiry wrapped up, the Commissioner lasted another eight years, but storm clouds grew forever more dark over Herchmer’s horizon. In the mind of Frederick White, and many others, the Commissioner’s end day was only a matter of time. And they were prepared to wait.

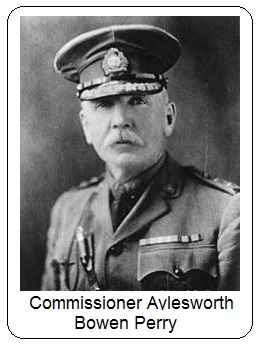

In 1900, Commissioner Herchmer requested permission to go to South Africa with the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles. Upon his arrival in South Africa, Herchmer was met with resistance. His superior Officer, British Major General Edward Hutton had formed the opinion that Herchmer was mentally and physically unfit to lead the Canadian Contingent. Herchmer fought to retain his authority and his position, but in spite of various tactics, it was of no use. He returned to Canada. In the meantime, John A. MacDonald had died, and upon his arrival to Canada, Sir Wilfrid Laurier relieved Herchmer of his stewardship as Commissioner of the NWMP. His fall was assured, and sudden, but not totally unexpected. He was replaced by Commissioner Aylesworth Bowen Perry. Herchmer left the Force sad, disenchanted and lonely.

Web2016.jpg)

Lawrence Herchmer spent the remainder of his life protesting all sorts of injustices, and trying to set the record straight. But, it was all for naught. His brother had died years before, and he had few remaining friends. In the end, apparently no one cared and there was no one to listen.

In fairness to the Commissioner, the following idea has to be given some consideration. Herchmer was appointed to the Commissioner's chair by the Prime Minister. It was a legitimate appointment, and Herchmer accepted the job with the thought that his services would be valued. It is acknowledged that he possessed an awkward and authoritative personality which was accompanied by a military bearing, but Herchmer likely did not realize the depth of resentment offered by the other Officers in the NWMP. They simply did not make his life easy. In that light, there is enough blame to be shared by both sides -- he on the one side and the Officer Corps on the other side. The conclusion of shared blame was essentially the same opinion reached by the judicial inquiry of 1892 which looked into Herchmer's conduct.

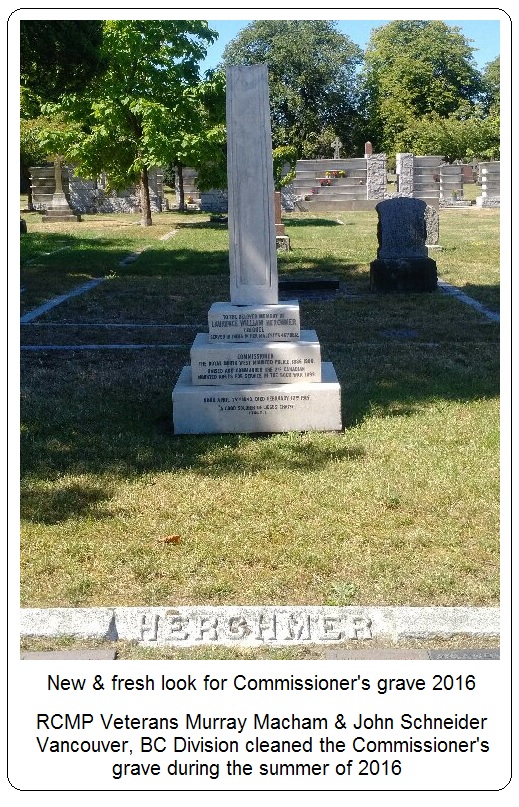

The Commissioner died in Vancouver, BC in February, 1915. He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery.

Commissioner Herchmer will forever be remembered as an exceptional and tough administrator; he reorganized the Force into a more efficient police organization, and he significantly improved living conditions, and benefits and training for his Officers and the men. Yet, he had to slug it out year after year. It is too bad that his quick temper and his overbearing personality resulted in so many enemies -- surely within the Officer Corps of the NWMP, but also within the community, business leaders, the press, and among influential politicians.

It is a full mystery as to how Commissioner Herchmer was able to remain in office for fourteen years.

The life and times of Lawrence Herchmer can offer contemporary police officers with a few short lessons. First, the RCMP Commissioner serves at the pleasure of the Prime Minister, and of Parliament. One must be prepared to listen to the winds and tides of democracy. Viable options are available to RCMP Officers who do not receive the nod of the Prime Minister for the Commissioner's job. The runner ups can either give the new appointee as Commissioner one hundred per cent support, or one can resign and thus follow the example of Assistant Commissioner Crozier. He set precedent in 1886.

Secondly, from time to time, the RCMP Commissioner can expect that he or she will come under attack from a wide host of sources; members within the RCMP itself, politicians, government agencies, TV and radio celebrities, civil right activists, senators, journalists, external advisory groups, the courts, and news outlets to name but a few. Sometimes, criticism from groups such as these may seem harsh, but it is important that it be accepted as cleansing, as well as beneficial and sometimes corrective. A person does not ease into the Commissioner's Office without being prepared for criticism.

And finally, every Commissioner ought to be reminded that his or her term of appointment should not be over extended by too much. After a spell of service, change at the top is always healthy for any organization whether people be in government or otherwise; administrators, business leaders, politicians or premiers, industry icons, sports figures or hockey coaches. Change at the top is equivalent to timely organizational renewal.

The end

Reporting from the Fort,

J. J. Healy

December 20, 2016

Atkin, Ronald. (1973). Maintain the right. MacMillan London, Ltd.

Deane, Richard Burton. (2001). Mounted police life in canada. Prospero Books. From the 1916 Cassell and Co. ed.

Denny, Sir Cecil E. (1939). The law marches west. Denny Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire. UK.