True and Fascinating Canadian History

Vet of the Month: March, 2020

The NWMP and Prairie Cold As A Foe

RCMP Vets. Ottawa, ON

Many of the early Officers and men of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) may have thought that the March West across the Canadian western plains over the summer and fall of 1874 would be filled with adventure and new hope. But, that turned out not to be the case -- very soon they discovered there was very little to dream about and instead the men faced hostile weather; unbearable summer heat, wind storms, lightning and freezing temperatures that led to injury and death among the men not only along the route to the west but even after they settled down permanently and the March West was over.

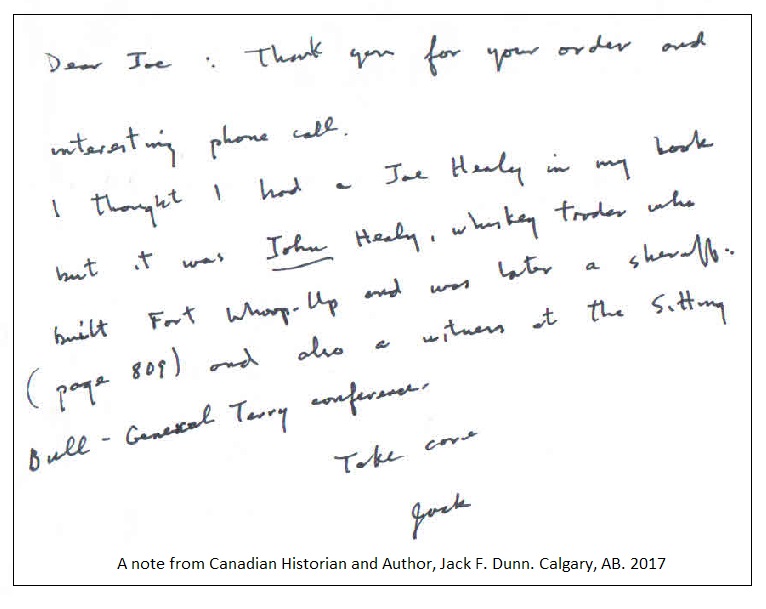

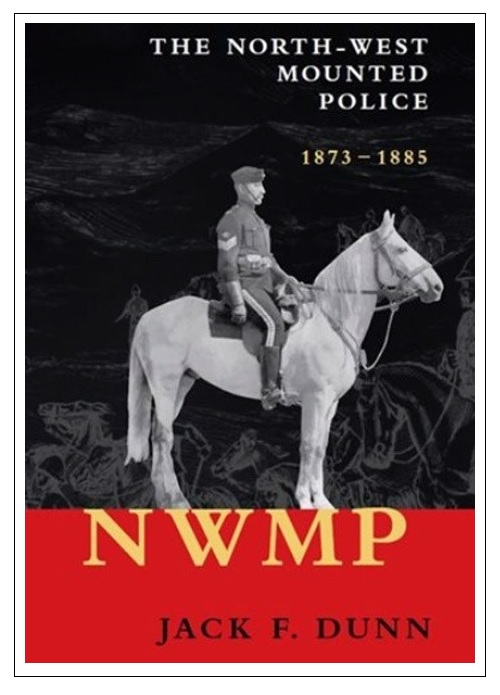

This short story is dedicated to some of the pioneer men of the NWMP who suffered immensely or lost their life due to the very hazardous weather conditions on the prairies, and unpredictable circumstances for which they were ill prepared such as the blinding effects of the sun off the snow. In his 2016 book entitled, The North-West Mounted Police: 1873-1885, Calgary historian and author Jack F. Dunn described the menacing after effects of snow blindness on the men. Dunn wrote, "A policeman who failed to take precautions against sun reflecting off the snow risked blindness...And twenty-two police became snow-blind on the march from Fort Qu'Appelle to Prince Albert days before the outbreak of the North-West Rebellion." (p. 68).

The men had not yet reached Prince Albert so under the circumstances, the only cure the Hospital Orderly could come up with was for the man to hold on to each other and continue to walk north until they reached their final destination. A mental image of the men marching in single file and holding on to each other might have looked like a scene out of a comedy act, but it was actually a practical and laudable survival tactic. Clinging to each other also saved their lives.

Freezing temperatures and snow storms in the winter months were an ever constant menace. In his haste to find protection from the unspeakable cold, Constable Kennedy once scouted ahead but became dangerously separated from his main party in a fierce snow storm. Author Jack Dunn wrote, "The winds increased in severity and the Mountie became lost and spent the night on the open prairie without even food or fire." (p. 69).

When Kennedy was found nearby the next day, he was still alive but frozen as stiff as a dropped puck in an NHL hockey game. Author Jack Dunn said Kennedy's ill thought out maneuver caught the attention of a Battleford newspaper who warned others in the community. The newspaper said, "It is hoped that this escapade will be a warning to others not to attempt to travel alone, even for a short distance during a North-West snow storm." (p. 69)

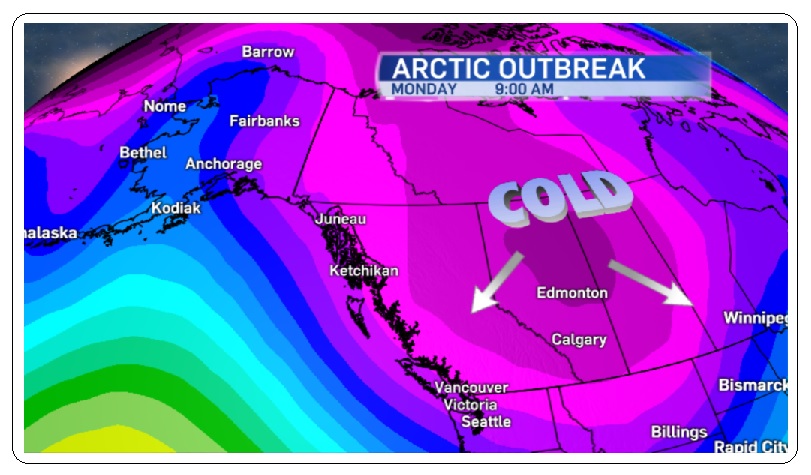

Cold temperatures on the prairies were unforgiving and made all aspects of daily life both dangerous and uncompromising. Wood and coal had to be stored to ensure the NWMP had sufficient supplies for the indeterminable long winters. Fire in their kitchen and parlour stoves provided warmth and around the clock fire stokers were employed to ensure the ambers were never allowed to completely go out.

Creativity and innovation was made to the customary police uniform; bulky buffalo coats and insulated moccasins and long underwear were issued to starve off the cold temperatures felt by everyone. Patrols on horseback were restricted and would only be allowed after every safety precaution was considered, but even so little things were sometimes overlooked. For instance, Jack Dunn humorously related this particular incident. Dunn wrote, "Sergeant Frank Fitzpatrick, assigned to take notes while on a winter tour of Indian reserves, had the ink bottle freeze in his saddle bag. Afterwards, he kept the ink bottle next to his body when riding." (p. 69) In future outings, no doubt Fitzpatrick gave acute consideration to and reviewed every possible risk to his duties whenever he was exposed to cold temperatures outside the Fort.

No one was immune to the unbelievable cold. One day, a constable came across a victim who was identified as an American army deserter. The constable helped the American reach Fort Walsh, but the camp cook recalled the poor man's fate. The cook said, "The poor chap was so badly frozen that the doctor could not help him and he died and his body lay just in a tent just outside my kitchen door with the tent flapping and the winter wind howling, it gave one an eerie feeling." (p. 70).

Deaths among the NWMP too were directly attributed to the weather. In his book, historian Jack Dunn cited the following cases where the cold was too much. He wrote, "Three mounted policemen froze to death. Sub-Constable Frank Baxter and T. D. Wilson died in a blizzard near Fort Macleod on December 31, 1874, Constable W. M. Ross died from exposure on January 1, 1885 in Kicking Horse Pass." (p. 70). Even if the best clothing had been provided to the men, the cold temperatures sometimes dropped so low that layered protection might not have saved their lives if they were exposed outdoors more than a few minutes.

Some men suffered from extreme and life long injuries which were also attributed to the inhospitable cold. Frost bite often lead to amputations, and one can well imagine that losing a limb was worse than falling asleep in the snow and dying. Historian Jack Dunn said that Constable Roger Pocock once neglected to remove his wet boots and his feet soon froze inside them and the boots had to be cut off with a knife. Pocock never recovered from his neglect. Dunn wrote, "At Prince Albert, a surgeon amputated all the toes on Pocock's right foot." (p. 70).

The practice of amputating body parts due to the frigid temperatures on the prairies continued on for many years. Men suffered excruciating pain. In his notes, now deceased RCMP Officer and Historian Jack White reported several cases of amputation. During the winter of 1877, Reg.#o401, Constable A. Elliott froze his foot and one big toe had to be amputated.

In the same winter, Reg.#1815, Constable Stephen Owens deserted the NWMP from Lethbridge and then fled to the USA. But, during his escape his feet froze so badly they both had to be amputated by US Army surgeons. The Canadian government felt sympathy because of Owens' plight, so Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald approved his discharge and Owens was allowed to remain in the USA.

In 1888, Reg.#1396, Constable George Cutler was searching for escaped prisoners on the Blackfoot Reserve when his right hand partially froze. Eventually Constable Cutler had part of his little finger amputated. He was granted $250.00 compensation for the loss of his little finger on his right hand. Nonetheless, for the remainder of his life the amputation would forever remind him of the freezing winter temperatures he once experienced on the prairies with the NWMP.

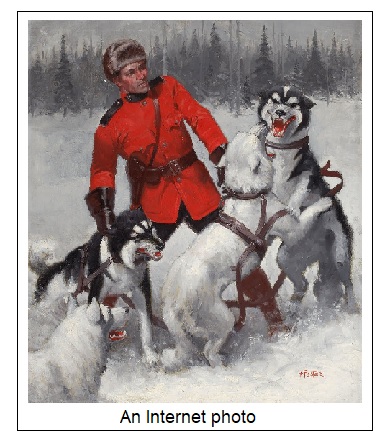

Sometimes the early history of the RCMP is portrayed in very glossy and unrealistic ways. In reality, the pioneers of the NWMP suffered in many ways and life was arduous and daily conditions were not at all pleasant. No doubt when a recruit received a transfer he could only hope that he was sent to a post where the weather was reasonably moderate.

The end.

Reporting from Fort Healy,

J. J. Healy

March 23, 2020

Dunn, Jack (2017). The North-West Mounted Police: 1873-1885. Self Published. Jack F. Dunn. Calgary, AB. Canada